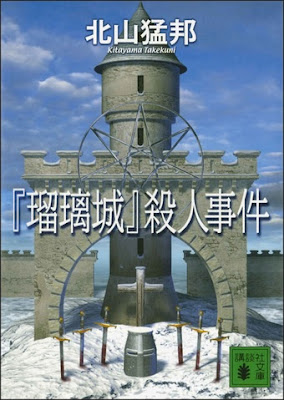

Last month, I reviewed Takekuni Kitayama's Rurijou satsujin jiken (The "Lapis Lazuli Castle" Murders, 2002), which came out of the first round of nominations for the new, up-to-date "Locked Room Library" and turned out to be available as a fanlation – translated by Mitsuda Madoy and "cosmiicnana." The "Lapis Lazuli Castle" Murders takes place in different time periods and places littered with seemingly impossible decapitations grandly tied together in the end. I summed it up as utterly insane in the most flattering sense of the word. So was curious to see what else they had translated and one title stood out. Surprisingly, it's not a locked room mystery or impossible crime novel!

I read about Jun Kurachi's Hoshifuri sansou no satsujin (Murders in the Mountain Lodges Beneath the Shooting Stars, 1996) when Ho-Ling Wong reviewed it back in 2021. Ho-Ling praised Murders in the Mountain Lodges Beneath the Shooting Stars as "a fantastic example of the logic school of mystery writing" that "challenges the reader to logically infer who the murderer is." The challenges begin the moment you open the book with each, lengthy chapters title summarizing what's going to happen in that chapter. For example, the first chapter is titled "First, we are introduced to the main character. The protagonist is the viewpoint character, or, alternatively, the Watson. In other words, they shall share all information they possess with the reader. They cannot be the culprit." Every other chapter ends with helpful pointer or comment like "there's important foreshadowing here" or "pay attention." That sure sounds suspiciously considerate and needlessly helpful. Surely, Kurachi isn't going to lie through his teeth by strictly speaking the truth? Let's find out!Kazuo Sugishita, the Watson of the story, works for the Production Department of Century Ad, but, after a work floor related incident with an assistant manager, Sugishita is temporarily moved to the Culture and Creative Department as a manager-in-training – except his duties turn out to be of an attendant. Shiro Hoshizono, the detective of the story, is a dandy, pompous self-styled Star Watcher, "he celebrated the beauty of the stars, talked about the night sky," whose books, horoscopes and TV shows are tremendously popular with the female demographic. A rising star developed in-house, but Sugishita thinks of Hoshizono as "an annoyance and a creep." However, Sugishita's first job as Hoshizono's attendant is accompanying him to a remote campground deep in the snowy mountains of Saitama Prefecture.

Century Ad also has a finger in the real estate business and is working together with a development company to redevelop the recently acquired Togaridake Lodge Village. A poorly thought out, ill-fated business venture that had gone bust due to its remoteness and lack of a special attractions. So the President of Yamakanmuri Development, Gozo Iwagishi, brings a select group to the campground to look over the lodges and spit balling ideas for a new concept to attract tourists. Akane Kusabuki, a popular romance author, and her secretary, Asako Hayasawa. Kazuteru Sagashima is a full-time UFO researcher who believes there's an alien base hidden somewhere deep in the mountains of Chichibu. Yumi Kodaira and Mikiko Ohinata are two college students who jumped on the opportunity to meet a couple of celebrities. And, of course, Sugishita and Hoshizono.

So the plan is to spend the night at, the soon to be renamed, Togaridake Lodge Village and brainstorming to make the impoverished-looking, desolate square of lodged and its two-story main building both appealing and profitable ("home of stars, romance, and UFOs"). Like having one of Akane Kusabuki's romance novels take place at the future star resort or a planetarium with recordings of Hoshizono lecturing on the constellations peppered with discussions on extraterrestrial visitors ("...did you know there are fragments of an enormous UFO mothership scattered in orbit?").

Kurachi takes his time working towards the murder, roughly the first-half, but everything leading up the murder is full with important information, clues, red herrings and foreshadowing – exactly as promised on the can (i.e. chapter titles). On the following morning, they find the beaten, strangled body of Gozo Iwagishi lying on the floor of his lodge. There are no phone lines and nobody brought along the cell phones on top of a minor avalanche that made the road below impassable. And, when they turn on the television, they learn a raging snowstorm has paralyzed the entire region with emergency services being overstretched. So the group is stranded for the time being, short on supplies and one of them is a murderer.

Murders in the Mountain Lodges Beneath the Shooting Stars has all the appearance of an extremely conventional whodunit, which has has a very obvious purpose. Kurachi basically removed all the short cuts.

I recently reviewed Seishi Yokomizo's Akuma no temari uta (The Little Sparrow Murders, 1957/59) and noted that it read more like a Western-style, Golden Age mystery than what we have come to expect from the recent run (shin) honkaku translations. Yokomizo simply wanted to read a Western-style mystery a la Agatha Christie and simply had no need for locked rooms, corpse-puzzles and other plot-oriented tropes. My love for these things have been well documented (fortunately, not by a psychiatrist), but it has to admitted that something like a locked room murder, dying message or a corpse cut to pieces often present a short cut to the solution or important parts of the solution – if you know the how it was done, you often know who done it. For example, I figured out the solution to Tetsuya Ayukawa's short story "Akai misshitsu" ("The Red Locked Room," 1954) because the murderer left a dismembered body inside a locked mortuary. Kurachi seems to have eschewed all the usual shin honkaku tropes, or short cuts, on purpose in order to make the whole thing as difficult as possible.

Murders in the Mountain Lodges Beneath the Shooting Stars has no locked room murders, dying clues, bombproof alibis, corpse-puzzles or a trail of bodies following a rhyming scheme. Just a small group of people in the middle of nowhere, cut off from the outside world, stuck with a body and killer. Kurachi took the isolated, closed-circle of suspects situation to its logical extreme as Hoshizono assumes the role of detective with Sugishita as his initially reluctant Watson.

Sugishita at first feels like "he'd been banished from his company to a frigid village with a gigolo," but, over the course of Hoshizono's investigation, begins to appreciate "the the brain behind his professional playboy front." So without an impossibility, dying message or tidy alibis to investigate ("...nobody has a perfect alibi"), they concentrate on the suspects and physical clues. And how! Hoshizono makes a lot about the three distinct lines of footprints going, or leaving, Iwagishi's lodge and the murder weapons. There is, what appears to be, a crop circle directly outside the lodge and a second murder involves an improvised "burglar alarm" that didn't work. If you like these in-depth investigations, you're certainly going to enjoy the discussions, weighing of evidence and possibilities – culminating in a lengthy, dizzying denouement. Hoshizono collected from the evidence and information six categories of clues, positional relationship, choice of weapon, alibi, psychological element, physical characteristics and action. One by one, Hoshizono begins to painstakingly eliminate suspects as he explains the murderer's movements and sometimes baffling actions on the nights both murders were committed. Like the creation of the snowy crop circle. Until apparently one person, the guilty party, remains, but there's a twist!

A pleasingly convincing, logically reasoned solution firmly positioned on, what John Dickson Carr called, a ladder of clues and pattern of evidence deceivingly arranged and logically joined together. In that regard, Murders in the Mountain Lodges Beneath the Shooting Stars is a triumph and a minor classic. A no-gimmicks-needed, simon-pure jigsaw puzzle detective novel with more than half a dozen diagrams to help out the struggling armchair detective. While playing absolutely fair in presenting a solvable whodunit, the misdirection was also on point and the honestly titled chapters were indeed about as helpful as a sandstorm in a labyrinth. Very well played!

So, plot-wise, nothing much to complain about, but stylistically and presentation-wise, it has one or two shortcomings. Firstly, if there ever was a detective novel that needed "A Challenge to the Reader," it is this one. It was just conspicuous in its absence here. Secondly, the story itself didn't feature an impossible crime, but the story mentioned an unsolved locked room murder in Hoshizono's backstory and a sequel was teased ("maybe someday, perhaps even someday soon, Kazuo and Hoshizono would journey to that village... to uncover the truth behind the locked room murder from nine years ago before the statute of limitations ran out"). Considering this is a standalone, published nearly thirty years ago, I doubt that case will ever be solved. I hate getting teased with non-existent locked room mysteries like that unrecorded Dr. Fell case of the inverted room at Waterfall Manor mentioned in Death Watch (1935). That and the current title is a bit of a mouthful.

Other than those minor issues, I agree with Ho-Ling that Kurachi's Murders in the Mountain Lodges Beneath the Shooting Stars is a must-read for fans of Ellery Queen and Alice Arisugawa's Koto pazuru (The Moai Island Puzzle, 1989). An extremely conventional whodunit, but a conventional whodunit playing the grandest game on hard mode. A grand performance that makes me wish people like Anthony Boucher and Frederic Dannay were still around to enjoy it. Highly recommended!

A note for the curious: I have mentioned more than once on this blog that it always surprised me that the traditional detective story, particularly impossible crime stories, rarely ventured outside haunted houses, rooms that kill and séance rooms whenever the plot calls for supernatural or otherworldly dressing. An impossible murder around a séance table remains a popular setup, even today, but expanding into other, post-Victorian-era myths and legends could give the impossible crime genre a whole new impulse. I always thought UFOs and everything associated with them is an untapped reservoir of potential for mystery writers specialized in locked room mysteries and impossible crimes. For example, the third story from Gosho Aoyama's Case Closed, vol. 89. You can find another small example in the snowy crop circle from this book, but just as interesting are the UFO cases the characters discuss because some could easily be the setup for an impossible crime story. Cattle mutilations in field with "no human footprints, tire tracks, or any other traces left at the scenes" or two farmers in New Zealand burned to death by aliens in a corn field in front of an astonished witness. Even better is "the Jessica Reid incident" whose bedroom was invaded by "an alien in a silver protective suit" who strangled her husband to death in a handful of seconds when they resisted ("...every shot bounced off the alien's suit"). Only downside to turning that one in a detective story is that the solution is rather obvious.