Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning were an American husband-and-wife writing team who got their start "as Roaring Twenties newspaper reporters" working "the mean moonlight and magnolia streets" of New Orleans, Louisiana, covering everything from the Great Mississippi River Flood to "bizarre and grisly killings" – providing them with first-hand experience for their detective novels. During the early 1930s, Bristow and Manning collaborated on four novels with the least obscure one being their first, The Invisible Host (1930).

The

Invisible Host is a pulp-style thriller and the only reason why

it wasn't completely forgotten is that some people have heralded it

as the inspiration of Agatha

Christie's And Then There Were None (1939). I read a Dutch

translation back in 2000s and dismissed it at the time as an awful

piece of crime fiction, but, when Dean

Street Press reprinted their novels last year, jubilant

reviews

of The Invisible Host began

to pour

in. More astonishingly, The Invisible Host defeated John

Dickson Carr's Till

Death Do Us Part (1944) with a 16 vote lead to win the 2021

Reprint of the Year Award. So did someone stuff the ballot box or

did I miss something on my first read? Maybe the problem was the

translation.

The

Invisible Host is a pulp-style thriller and the only reason why

it wasn't completely forgotten is that some people have heralded it

as the inspiration of Agatha

Christie's And Then There Were None (1939). I read a Dutch

translation back in 2000s and dismissed it at the time as an awful

piece of crime fiction, but, when Dean

Street Press reprinted their novels last year, jubilant

reviews

of The Invisible Host began

to pour

in. More astonishingly, The Invisible Host defeated John

Dickson Carr's Till

Death Do Us Part (1944) with a 16 vote lead to win the 2021

Reprint of the Year Award. So did someone stuff the ballot box or

did I miss something on my first read? Maybe the problem was the

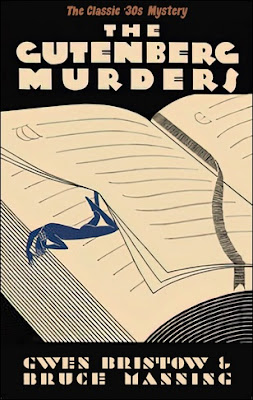

translation.Either way, the positive reactions reintroduced Bristow, Manning and The Invisible Host to my to-be-read pile to see what all the excitement is about, but decided to begin with their more formal, traditionally-styled detective novels – which happen to be part of a two-book series. The Gutenberg Murders (1931) and The Mardi Gras Murders (1932) share a small cast of characters, "both major and minor," who play the role of detectives and associates. I really was torn between the two as the introduction, written by Curt Evans, promised "a locked room killing on a parade float" in The Mardi Gras Murder. This time, I didn't want to be that predictable, chronologically challenged and obsessed locked room fanboy. So I settled on The Gutenberg Murders. Yes, it was a vast improvement on their maiden effort.

The Gutenberg Murders introduces the district attorney of Orleans Parish, Dan Farrell, who's not a brilliant man, but he has "a good deal of respect for the sort of learning which he regarded as a mental luxury." So he's not above consulting the ace crime reporter of The Morning Creole, Wade (no first name given). They're respectively assisted by Captain Dennis Murphy of the New Orleans Homicide Squad and the Creole's impish star photographer, Wiggins.

Dan Farrell is completely puzzled by the Quentin Ulman case. Quentin Ulman, assistant librarian of the Sheldon Memorial Library, is "an unusual man" suspected of "an unusual crime" and is suspected of "robbing the library for the past six months" of its valuable treasures. The latest theft was of nine recently acquired, highly prized leaves from the Gutenberg Bible, which were the pride and joy of the head librarian, Dr. Julian Prentiss. So he brought the case to the district attorney, but he doesn't want Ulman arrested. Just the return of the stolen books and his precious Bible fragments, but complicating an apparently simple case of theft is that the library is caked in dirt.

The head trustee of the library and Dr. Prentiss' longtime rival, Professor Alfredo Gonzales, whose twenty year long squabble with the head librarian came to a head when he voiced his suspicion the Gutenberg fragment was not genuine – indirectly accusing Prentiss having been fooled into buying a forgery. But there's also talk of Gonzales charming, much younger and "not very discreet" wife, Winifred, has gotten herself involved with Ulman. This is practically public knowledge and there are "whispers that Ulman sold the damn thing to buy pearls for Mrs. Gonzales," which stung her husband "where it hurts a Cuban gentleman worst." And there are the other people who hang around the library who either hold something back or simply cause trouble. Terry Sheldon is a sculptor and nephew of the library's founder, but the impulsive sort with a short temper. Luke Dancy is the personal secretary of Dr. Prentiss and "one of the regular American-Anglomaniac school" who dressed English and speaks with London-borrowed phrases. Marie Castille is a medical student who works at the library during the summer months and a distant cousin of Professor Gonzales. All of them hold something back or have something hide.

So more than enough material to complicate a simply, straightforward case of theft and fill a front page, or two, but, before the investigation can even begin, Ulman is murdered. Ulman's "charred and smoking skeleton" is found on a dirt road near the bindery. And thus began the Bible Murder Case.

Dan Farrell takes the unusual decision to deputize Wade and gave him a "tin badge" to act like a French juge d'instruction (examining magistrate). Wade gets a free hand to act as he sees fits from questioning suspects, as he tries to pry loose their jealously guarded secrets, to handling evidence, testing alibis and rooting around for motives – even threatening to arrest people or place them under police protection. One chapter details a gross invasion of privacy when Wiggins and his noiseless camera invade a home to secretly eavesdrop on a private conversation, which is of course used. So a little improbably, but sort of works with New Orleans as a backdrop. Since everyone insists on holding back important, even dangerous information, the torch murders continues with the third murder being a quasi-impossible crime. Every suspect has "a cast-iron alibi furnished by members of the police department."

Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning came up with a fascinating solution to the torch murders that should have been used to turn the story into a full-blown impossible crime novel. Fittingly, Wade pieces together the murder method after reading Euripides and Eusebe Salverte's The Philosophy of Magic, Prodigies and Apparent Miracles (1829). Only acceptable place to the find answers in a bibliophile mystery. However, Bristow and Manning also plotted the story along a straight, narrow line that glossed over a few details and didn't ask some very obvious question.

For example, the medical and forensic examinations of the victims (i.e. how they were set ablaze) was deliberately kept vague, because a thorough examination would have solved too much too soon. In the hands of the Radfords, The Gutenberg Murders would probably have been a short story instead of a novel-length mystery. Secondly, it's established with Quentin Ulman's death that the murderer hadn't burned the body to conceal his identity. Ulman was identified by items found on the body and it was suggested the murderer wanted to make him "a hideous memory," but nobody thought of the possibility that Ulman could have staged his own death. After all, Ulman was suspected of having stolen a small fortune in antiquarian treasures. So why not try to shake everyone off his back once he realized the game was over and start over somewhere else under a new name and nice little nest egg. A possibility destroyed by the second and third murder, but it takes a while to get to them and it's just weird nobody considered the possibility until the other murders happened.

Nitpicking aside, The Gutenberg Murders is a massive improvement over what I remember of The Invisible Host. A well-written, competently plotted detective novel with an unusual piece of detective work that nonetheless logically tied together the who, why and how. A solution both logical and not wholly unsatisfying, but lacked a bit of a punch. So not a first-rate specimen of the vintage detective novel, but another good and solid second-stringer that comes particularly recommended to fans of biblio mysteries. More importantly, The Gutenberg Murders has convinced me to move The Mardi Gras Murders and Two and Two Make Twenty-Two (1932) up a few places on the big pile. Redemption might be imminent!

And on a final note, I have come across a lot of good, but second-string, mysteries lately and will try to pick a title from the top-tier next time.

And all the people who loved Host seemingly hated Gutenberg! On the other hand I have noticed that people who hate Host tend to like Gutenberg. So go figure, maybe it's like ink blot tests. Mardi Gras has some similarity to Carr (Corpse on the Waxworks), but don't pin too much hope on the locked room situation! On the other hand I thought Twenty-Two had a really nifty solution. Fooled me, anyway!

ReplyDeleteI also noticed that people who loved The Invisible Host tend to be a lot more critical of the same shortcomings in other pulp-style mysteries, if they don't ignore the pulps altogether. For example, Jim's takes on John Russell Fearn. ;) I guess its passing resemblance to And Then There Were None was enough of a distraction to fool some into believing it's actually good. But who know. I might end up eating my own words when it gets a second look.

DeleteOh, TomCat, TomCat, TomCat! I don't have an issue with you hating The Invisible Host, but that you found Gutenberg to be "better" totally baffles me. At any rate, I will be reading Twenty-Two one of these days and will hope that it succeeds where the Bible murder case failed for me.

ReplyDeleteThe Invisible Host and Two and Two Make Twenty-Two appear to the two popular of the four reprints. So my next stop is definitely going to be The Mardi Gras Murders.

Delete