This

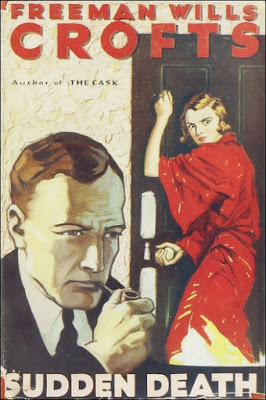

year, the Collins

Crime Club imprint, of HarperCollins, reissued six long

out-of-print novels by Freeman

Wills Crofts in two batches of three with the second batch

comprising of Mystery on Southampton Water (1934), Crime at

Guildford (1935) and the novel that has been on my wishlist for

ages, Sudden Death (1932) – which is Crofts' take on my

beloved locked

room mystery. Inspector Joseph French has build a reputation on

being "invariably sceptical of alibis" and breaking them

down with painstaking work and dogged determination. Sudden Death

demonstrated French is as adept at tearing down locked rooms as he is

at disassembling faked alibis with no less than two impossible

murders coming his way!

Sudden

Death also showed Crofts could be more, if he wanted to be, than

a plot-technician with the story's viewpoint alternating between

French and a young woman, Anne Day.

Sudden

Death also showed Crofts could be more, if he wanted to be, than

a plot-technician with the story's viewpoint alternating between

French and a young woman, Anne Day.

Anne

had spent most of her early life in an old Gloucester parsonage

attending her reclusive, scholarly father, Reverend Latimer Day, but

when he passed away, she was left homeless with "an income of

barely thirty pounds a year" – only lucky enough to find a

job as a companion to an elderly lady. But when she died, a then

28-year-old Anne was forced back to the registry offices of London

with no special qualifications while "shoes and gloves, and

latterly even food and lodging" becoming "more and more

hideously insistent problems." One day, Anne is offered a

position in the home of Severus Grinsmead to help his sick,

semi-invalid wife, Sybil, run the household. A well paid position

with a very generous advance. Naturally, not everything is as rosy as

it seems.

Surprisingly,

coming from Crofts, there's a hint of The

Had-I-But-Known School in the opening chapter with the line "had

she known all that awaited her at Ashbridge," she "might

well have drawn back in dismay" from "the agonies of fear

and horror and suspense which she was fated to endure with the

Grinsmeads."

Sybil

is a sickly, cold and deeply suspicious woman and it takes Anne some

time to gain her confidence, but she didn't need it to understand

that the relationship between husband-and-wife resembles that of an

armed truce between two hostile nations. Sybil is aware her husband

is having an affair with the local grass widow, Irene Holt-Lancing,

which convinced her that they want her dead and biding their time for

the right moment – ensuring Anne there will be an accident or "it

may look like suicide." Puzzling, Anne becomes privy of

evidence and information both confirming and contradicting Sybil's

deadly fears. I think False Impressions would have been a

better title than Sudden Death, because it fits so many

aspects of the plot and story.

Nevertheless,

not everything is laden with impending doom or suspicion. Anne comes

to find out that the governess to the Grinsmead children, Edith

Cheame, shares a similar life story to her own and that Severus

Grinsmead's mother is not quite as stiff or censorious as Sybil made

her out to be. She also strikes up a friendship with the children and

gets on with the chauffeur/gardener like a house on fire. So she

could almost forget her employers unhappy marriage, infidelity and

suspicion, but that all changes one morning when Anne went to her

bedroom to bring her tea. Anne's knocking remained unanswered by the

invitational click of the electric, push-button operated bolt. She

then noticed that there was "an odd smell of gas" in the

corridor and quickly realized "gas was simply pouring out"

of the keyhole of Sybil's room. A hammer and chisel were needed to

demolish the lock and open the solid door, but help had arrived too

late. Inspector Kendal, of the local police, goes over the room with

a fine tooth comb, but finds "an enclosed affair" that "you couldn't very well temper with." So concludes it was

a suicide and that's the verdict at the inquest.

There

are, however, some minor details bothering Kendal and Scotland Yard

assigned Inspector Joseph French to the case to go over all the

details again and give them a second opinion. I suppose this is where

people who dislike Crofts will very likely stop liking Sudden

Death.

Crofts

tried to write a novel of character (singular) with Anne Day as in

the lead during the first third of the story, but French's thorough

and painstaking investigation of the locked room problem proved his

heart lay with the nuts and bolts of the plot – coming up with a

number of ways to gas someone behind a locked door. My fellow

impossible crime enthusiast and Crofts aficionado, "JJ” of The

Invisible Event, suggests in his

review that "dazzling array of options" can be counted

as "a Locked Room Lecture that predates that of The Hollow

Man (1935) by John

Dickson Carr," but

Crofts is "less showy" about it. For once, I've to agree

with JJ. Crofts doesn't break the fourth wall to acknowledge the

reader and it's not presented as a lecture, but it can be read as a

proto-Locked Room Lecture. Something that will no doubt please anyone

with a special affinity for impossible crime fiction.

Another

thing that occurred to me while reading is Crofts might have created

the most convincing and believable of all so-called fallible

detectives. Anthony

Berkeley usually made an ass out of Roger Sheringham (e.g.

Jumping

Jenny, 1934) and Ellery

Queen too angsty (e.g. Ten

Days' Wonder, 1948), but Crofts created a competent,

intelligent and imaginative Scotland Yard inspector, which are

admirable qualities, but they come without cast-iron guarantees of

success attached to them. French is not an enigmatic detective who

can deduce the truth from a bowl of daffodils or the curious incident

of the dog in the nighttime, but he does use the Sherlockian inspired

method of rejecting the impossible and "see what is left."

A thorough, painstaking process of elimination and fine-tuning of

possibilities that has many dead ends and constant second guessing

whether, or not, he was building his theories on "an foundation

of sand." And it was a nice touch by making French sink his

teeth in the case with a future chief inspectorship in the back of

his mind.

You

can, however, argue French came up a little short on this occasion

with only a second death preventing a terrible mistake when one of

his main suspects committed suicide in a room with all the doors and

windows locked, or fastened, on the inside – forcing him to go back

to the drawing board and start over again. So how good is Sudden

Death as a locked room mystery novel with its two

murders-disguised-as-suicides in completely locked rooms? Well, not

too badly!

The

solution to Sybil's murder in her locked bedroom is, to my knowledge,

original and don't believe it has been used since, but, as you can

probably guess, the trick is a technical, semi-mechanical nature. Not

everyone is going to like it. The solution to the second

impossibility is an old dodge of the locked room story, but it was

put to good use and provided the story with a last clue to the

murderer's identity. So, on balance, Sudden Death is not a

classic of its kind, but as a good and solid take on the impossible

crime novel. And not one that should be solely judged on the content

of its locked rooms.

Crofts

was one of the often maligned, so-called humdrum writers who were

more interested in the how than the who-and why, which means that

their murderers tend to be easily spotted. I wrongly assumed that the

case here, but the murderer and motive were cleverly hidden with "the

closed room as a blind." Crofts knew what makes a sound plot

tick and that makes it the more baffling he left a small aspect of

the first locked room murder unexplained. I can accept that from a

mystery writer who's more interested in character or storytelling or

a second-stringer, but the Chief Engineer of Crime should have known

better and it seriously detracted from, what would otherwise have

been, the best Inspector French novel to date. Now I have to

reluctantly place it slightly below The

Sea Mystery (1928), Mystery

in the Channel (1931) and The

Hog's Back Mystery (1933).

Omission

not withstanding, Sudden Death is a fine piece of

old-fashioned, Golden Age craftsmanship and it was fun to see the

master of the unbreakable alibi apply himself to the locked room

mystery while dabbling a little in domestic suspense and HIBK. Sudden

Death shows Crofts is as deserving of being revived as he was

undeserving of his old reputation as the writer who cured insomnia.

Now all I want is a reprint of Crofts' second locked room novel, The

End of Andrew Harrison (1938), but until then, my next stop in

the series is probably going to be Sir

John Magill's Last Journey (1930). So stay tuned!

I'm pleased you got mostly good things out of this, and that you see my point about the proto locked room lecture. It was a lot of fun seeing Crofts turn his mind to the Country House Mystery. I wonder if he wrote another one after this and The Ponson Case (1921)?

ReplyDeleteThe second locked room is an intriguing one. This was originally published as a Harper Sealed Mystery, where a seal holding the pages containing the solutions had to be cut open if you wished to find out the answers. Since the first locked room is explained early and only the second remains, I wondered how original this solution was in 1932. You wouldn't put something so hoary in a book that prided itself on being gripping and baffling in the final stages now, would you? That solution has become old hat now, of course, but back then it might have been the hippest new thing on the block.

Very excited to see what you make of John Magill...

This will probably damage my reputation as the resident locked room fanboy, but I'm sure the second locked room-trick was used before 1932 without being able to cite any examples off the top of my head. I think it might have been used in one or two pre-1932 short stories. But if I'm wrong, props to Crofts for coming up with such a simple, one-size fits-all solution to the locked room problem that it has been used for nearly a century now.

DeleteEither way, your enthusiasm for Crofts is more than justified. He was one of the greatest!

If it's any consolation, I could think of no examples of it either. I've not got quite your coverage of the impossible crime in fiction, but I like to think that if there was an obvious example we'd be able to come up with it between us...:

DeleteHow nice to see Inspector French revived. My husband and I read Crofts avidly years ago, and I still remember The Pit Prop Syndicate as one of his best. As an engineer, Crofts insisted that his solutions be plausible and doable, and I enjoyed watching him work out tide tables, shipping information, etc. Yes, it's time he took his place among the greats.

ReplyDeleteCrofts first revival in the very early 2000s was short-lived and those House of Stratus editions have already become ridiculous expensive collector items, which makes it so gratifying that this second revival is such a success and rehabilitated his reputation. A much earned rehabilitation!

DeleteI like your nickname for him as "Chief Engineer of Crime." Raymond Chandler also thought so.

ReplyDeleteCrofts' realistic policework and investigations was apparently a huge influence on American hardboiled writers like Chandler and Hammett. Mike Grost has written about it on his website: mikegrost.com/hammett.htm and mikegrost.com/chandler.htm

DeleteA thorough, painstaking process of elimination and fine-tuning of possibilities that has many dead ends and constant second guessing whether, or not, he was building his theories on "an foundation of sand." And it was a nice touch by making French sink his teeth in the case with a future chief inspectorship in the back of his mind.

ReplyDeleteThey're the two things I love most about French - his painstaking methods and his hunger for promotion.

but until then, my next stop in the series is probably going to be Sir John Magill's Last Journey (1930).

My favourite Crofts so far. It's so very very Croftsian.

My impression is that Sir John Magill's Last Journey is to Crofts what The Hollow Man is to Carr or Death on the Nile to Christie. Very much look forward to reading it!

DeleteCrofts often resorted to HIBK in his books!

ReplyDeleteShows how little I've read by Crofts. Yes, I know. Heresy.

Delete