"How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?"- Sherlock Holmes (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Sign of Four, 1890)

Martin

Edwards is a decorated crime novelist, genre-historian and author

of the award-winning The Golden Age of Murder (2015), which I

still haven't read, but currently he's also engaged as the resident

anthologist of the British Library – compiling such themed

anthologies as Resorting

to Murder: Holiday Mysteries (2015) and Crimson

Snow: Winter Mysteries (2016). Last week, the greatest title

in the series yet rolled off the printing presses.

Yes,

that's my personal, opinionated bias bleeding through. I love locked

room mysteries. Deal with it.

Miraculous

Mysteries: Locked Room Murders and Impossible Crimes (2017)

gathered sixteen short stories that were never, or rarely, collected

in similar themed anthologies.

A good portion of the stories came from the hands of such luminaries

as Conan

Doyle, G.K.

Chesterton and Dorothy

L. Sayers, but Edwards complemented their work with several

obscure, long-overlooked impossible crime tales by Grenville Robbins,

Christopher

St. John Sprigg and E. Charles Vivian – resulting in a

pleasantly balanced collection of short stories. So let's take a

closer look at the content of this newest anthology of miracle

crimes.

Miraculous

Mysteries: Locked Room Murders and Impossible Crimes (2017)

gathered sixteen short stories that were never, or rarely, collected

in similar themed anthologies.

A good portion of the stories came from the hands of such luminaries

as Conan

Doyle, G.K.

Chesterton and Dorothy

L. Sayers, but Edwards complemented their work with several

obscure, long-overlooked impossible crime tales by Grenville Robbins,

Christopher

St. John Sprigg and E. Charles Vivian – resulting in a

pleasantly balanced collection of short stories. So let's take a

closer look at the content of this newest anthology of miracle

crimes.

However,

I gave the following handful of stories a pass, because I didn't feel

like re-reading them or discussed them previously on this blog: Conan

Doyle's "The Lost Special," William Hope Hodgson's "The Thing

Invisible," R. Austin Freeman's "The Aluminium Dagger,"

Nicholas Olde's "The

Invisible Weapon" and Michael Innes' "The

Sands of Thyme." Even with these stories eliminated from the

line-up, this is still going to be one of those bloated blog-posts

that grows at the same speed as Erle Stanley Gardner's bibliography.

Strap in, everyone. This is going to be a long ride!

So

that makes the first story under examination Sax Rohmer's "The Case

of the Tragedies in the Greek Room," originally published in the

April 1913 issue of The New Magazine, which starred one of his

obscure, short-lived series-character, Moris Klaw – whose cases

were collected in The

Dream Detective (1920). Klaw is an antique dealer and an

occult detective who prefers to spend the night at the scene of a

crime, which reproduces clue-like images of the victim's last

thoughts in his dreams (hence the book-title). Scene of the crime in

this series-opener is the Greek Room of the Menzies Museum.

A

night attendant got his neck broken in the Greek Room, but how an

outsider could've entered and left the premise is a complete mystery.

There are only two entrances to the room, a public and a private one,

which were both securely locked and the windows were fitted with iron

bars. And there was no place where even "a mouse could find

shelter." Klaw is allowed to camp out in the room and received

a psychic photograph "a woman dressed all in white," but

also got the impression the night watchman had a "great fear for

the Athenean Harp" - a gemstone in the museum's collection.

Honestly, I did not expect too much from this story, but, while

dated, the plot was fairly decent and well-put together. Granted,

some of the finer details about the exact cause of death and murder

method were as ridiculous as they were dated.

However,

as much as some aspects of the explanation stretches credulity, they

were still surprisingly down to earth for a detective story from an

occult mystery series. I also have to earmark the impossible problem,

and its solution, as an early example of a particular type of

impossibility that would turn up again in the works of John

Dickson Carr, Ken

Greenwald and David

Renwick.

The

next entry is one of favorite stories from G.K. Chesterton's

celebrated Father Brown series, "The Miracle of Moon Crescent,"

which came from a collection of short stories saturated with

impossible crime material – aptly titled The Incredulity of

Father Brown (1926). I've always been fond of this story on

account of the originality and brilliance of its locked room problem.

A

problem concerning the miraculous disappearance of an American

philanthropist, Warren Wynd, who vanished from a watched room on the

fourteenth floor of the apartment complex called Moon Crescent.

Equally inexplicable is his reappearance at the end of a rope in the

garden below. Luckily, Father Brown is at hand to alleviate the minds

of the baffled, "hard-shelled materialists" that were

present outside of Wynd's room and explain this apparent miracle. The

priest based his explanation on a madman he had seen firing a blank

at the building, which told him how the philanthropist was whisked

away from a closely observed room and why he was found hanging from a

tree branch. Absolutely ingenious! Only weakness of the plot is the

rather silly, far-fetched motive, but even that was somewhat

original.

Marten

Cumberland's "The Diary of Death" was first published in The

Strand Magazine of January, 1928, which has a premise that

should've been explored at novel length: a once popular musical

singer, Lilian Hope, had disappeared from the spotlight into "obscurity and direst poverty" - where "she died in a

miserable garret." During her waning years, Hope kept a diary

in which she poured out "vindictive and bitter accusations"

against her former friends. Naming everyone who she felt had

abandoned her and refused any kind of help. Someone got a hold of

this diary and begins to extract revenge on everyone mentioned in it.

Leaving behind a torn page from the diary after every murder.

So

the police have their hands full with the "Death Diary Murders,"

but the one who gets an opportunity to put a stop to the killings is

an amateur criminologist, Loreto Santos. At a house party, Santos is

approached by the person who's "next on the list," Sir

George Frame. He used be a friend of Hope, but the money he mailed to

the poor woman was intercepted by his wife. So she never received an

answer or a penny and dedicated some bitter words to Sir George in

her diary. And now he has received a torn page in the mail.

Sadly,

Santos is unable to avert Sir George's impending doom, because the

following morning they've to batter down the locked-and bolted door

of his bedroom door with a Crusader's mace and they find his body in

the middle of the room – a knife-handle protruding from his back. A

story with an intriguing and solid premise, however, its resolution

was a bit too simplistic. I easily spotted the murderer and the

problem of the locked room hinged on an old trick (c.f. "The Locked

Room Lecture" from Carr's The

Hollow Man, 1935), but still found it an enjoyable story.

Grenville

Robbins' "The Broadcast Murder," originally published in

Pearson's Magazine of July, 1928, which is one of the earliest

examples of a detective story set in the world of radio. I think the

story also demonstrate that mystery writers from the first half of

the twentieth century had no problem incorporating new technologies

into their plot. In this case, hundreds of thousands listeners heard

how the radio announcer suddenly yelled "help!" followed

by "the lights have gone out" and "someone's trying

to strangle me," but the fate of the announcer remains unknown

– since his body disappeared from "a hermetically sealed

studio." The trick is relatively simple one, using

old-fashioned misdirection, but the reason for staging such an

illusion at a radio studio shows the Golden Age was about to go in

full bloom.

Robert

Adey's Locked Room Murders (1991) lists a second short story

by Robbins, "The Broadcast Body," which was published in the

June, 1934, issue of 20-Story Magazine and deals with a

professor who vanished from a guarded room "in which he was

carrying out a matter-transference experiment." So that might

be a potential candidate for inclusion in a future anthology of this

kind.

The

next story, "The Music Room," was lifted from the pages of the

pseudonymous Sapper's

Ask for Ronald Standish (1936), which reportedly collects some

of his more detective-orientated crime-fiction and features his

second-string sleuth, Standish.

The

next story, "The Music Room," was lifted from the pages of the

pseudonymous Sapper's

Ask for Ronald Standish (1936), which reportedly collects some

of his more detective-orientated crime-fiction and features his

second-string sleuth, Standish.

Standish

is a guest at a, sort of, house warming party during which the host,

Sir John Crawsham, entertains the party by telling about an unsolved

mystery that came with the property. Nearly half a century ago, the

then lodge-keeper found the body of an unknown man in the music-room, "lower part of his face had literally been battered into a

pulp," but the real mystery is how his assailant could have

entered or left the room – because the door had to be broken open

and the key was on the inside of the door. As to be expected, someone

else dies inside the locked music-room, crushed by a chandelier,

before too long.

However, the explanation is hardly inventive and

even a bit disappointing, but appreciated how the potential presence

of a hidden passage was used. Otherwise, it's not really a remarkable

story at all.

Back

in 2015, Christopher St. John Sprigg's Death

of an Airman (1935) was republished as a British Library

Crime Classic and this brand new edition was as well received as the

original edition. So readers might be glad to know that this

anthology contains one of his obscure short stories.

"Death

at 8:30" was salvaged from the pages of the May 25, 1935, issue of

Detective Fiction Weekly and can be classified as a

sensationalist thriller with a mild puzzle plot, similar to Anthony

Berkeley's Death

in the House (1939), but superior in every way imaginable –

one of them being is that this story does not overstay its welcome. A

murderous blackmailer, known only as "X.K.," demanded exorbitant

sums of money in exchange to be left alone, but, when a victim

refused, they would be swiftly dispatched to the Great Hereafter.

There were three men who refused to comply with the demands and they

were all murdered under mysterious circumstances. The fourth person

who refuses to pay is no less a figure than the Home Secretary, Sir

Richard Jauntley, which demands extreme and extraordinary security

precautions.

The

vaults of the Bank of England was put at their disposal and the Home

Secretary was encased in "a cell of thick bullet-proof glass,"

surrounded by armed men, but, at the time announced by “X.K.,”

the Home Secretary began to writhe in agony and died within mere

seconds – poisoned! However, there were no apparent ways of how the

poison could have been introduced inside the sealed, bullet-proof and

air-filtered glass tube. One that was located in a sealed and heavily

guarded bank vault. I suppose I've been reading too many impossible

crime stories, because I immediately spotted the tale-tell clue that

told me how it was done. But how the murderer was dealt with was

something else all together. So, yes, not bad for a sensational

thriller story.

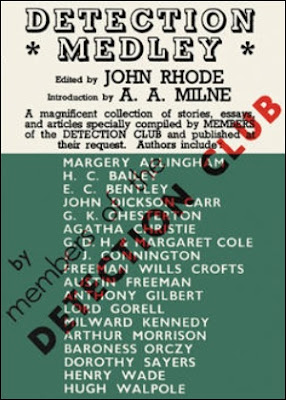

G.D.H.

and Margaret Cole's "Too Clever by Half" was included in The

Detection Club's Detection

Medley (1939) and is a semi-inverted mystery, in which the

narrator, Dr. Benjamin Tancred, tells about a clever murderer he once

met.

Samuel Bennett was the brainy licensee of the "Golden Eagle,"

an inn in the remote Willis Hill, where he was in the process of

murdering his brother-in-law when Dr. Tancred turned up. The victim

was found in an upstairs bedroom, locked from the inside, with a

bullet-hole in his head. On the surface, it looks like a simple case

of suicide, but Dr. Tancred suspects murder based on the inn-keepers

behavior, a lighted keyhole, the angle of the fatal bullet and the

smell of gun powder in the corridor.

This

is not really a story that allows you to puzzle along with the

detective, but it's fun to watch the detective dismantle, what could

have been, a clever and near perfect murder without breaking a sweat.

E.

Charles Vivian's "Locked In," originally collected in My Best

Mystery Story (1939), was a disappointing and forgettable tale of

a supposed suicide in a locked room. I did not care for it. Moving

on...

Dorothy

L. Sayers' "The Haunted Policeman" was first published in the

February, 1938, issue of Harper's Bazaar and was posthumously

collected in Striding

Folly (1971), but remains one of her most criminally

underrated pieces of fiction. The story represents one of her most

imaginative and strongest puzzle-plot, which could easily have been a

Carter Dickson yarn in The

Department of Queer Complaints (1940)!

The

story opens on the night when Lord Peter Wimsey's first son is born

and, shortly thereafter, meets a confused policeman. One who has a

very interesting ghost story to tell. P.C. Alfred Burt was pounding

pavement in Merriman's End, "a long cul-de-sac," where his

eye fell upon "a rough-looking fellow" in "a baggy

old coat" was lurking suspicious in the shadow, but when he was

about to ask the character what he was doing when someone yelled

bloody murder – which seemed to come from Number 13. Nobody

answered the door. But the policeman did take a peek through the

letter-flap and saw a man laying the hall with a carving-knife in his

throat. However, when he returned, alongside a colleague, all of the

houses in the street have even numbers. There's no number 13! And

none of the house they visited have an interior that resembles what

he observed through the letter-flap. The house, alongside the body,

vanished into the dark of the night.

The

explanation for this apparent impossibility is as satisfying as it's

cleverly simple. And, as noted here above, the plot of the story is

very Carrish in nature and could have easily been a case for Colonel

March of Department D-3. After all, he handled a similar kind of

problem in "The Crime in Nobody's Room."

The

next story is Edmund Crispin's "Beware of the Trains," originally

published in The London Evening Standard in 1949, which has

Gervase Fen assisting his policeman friend, Detective-Inspector

Humbleby, when a motorman disappeared from a moving train. At the

same time, the police had surrounded the small station to collar a

burglary. So nobody could have slipped out unobserved. A well-known

and competent enough story, but hardly one of Crispin's best

impossible crime stories. There are a pair of lesser-known, but far

stronger, locked room stories in Crispin's repertoire, namely "A

Country to Sell" and "Death Behind Bars," which appeared in a

posthumous collection – entitled Fen

Country: Twenty-Six Stories (1979). Hopefully, one of them

will be considered for a future anthology of locked room mysteries.

The

next story is Edmund Crispin's "Beware of the Trains," originally

published in The London Evening Standard in 1949, which has

Gervase Fen assisting his policeman friend, Detective-Inspector

Humbleby, when a motorman disappeared from a moving train. At the

same time, the police had surrounded the small station to collar a

burglary. So nobody could have slipped out unobserved. A well-known

and competent enough story, but hardly one of Crispin's best

impossible crime stories. There are a pair of lesser-known, but far

stronger, locked room stories in Crispin's repertoire, namely "A

Country to Sell" and "Death Behind Bars," which appeared in a

posthumous collection – entitled Fen

Country: Twenty-Six Stories (1979). Hopefully, one of them

will be considered for a future anthology of locked room mysteries.

Finally,

we have the youngest story in the collection, Margery

Allingham's "The Villa Marie Celeste," which was first

published in the October, 1960, issue of Ellery Queen's Mystery

Magazine. Personally, I'm not really a big fan of Allingham, but

this has to be one of the niftiest domestic mysteries I ever came

across. A young couple, married for three years, disappeared from

their comely home in Chestnut Grove. They apparent vacated a

half-eaten breakfast on a washing-day, took some sheets and vanished "like a stain under a bleach." Technically, this story

does not really qualify as an impossible crime, but the quality of

the story makes that a forgivable offense.

Some

of you might want to know that the unusual, but original, motive

makes it a close relative of a genuine locked room mystery from the

1980s, "The Locked Bathroom" by H.R.F. Keating, which I reviewed

here.

Funnily enough, both stories have a solution that involves laundry.

Mercifully,

that brings us at the end of this bloated, drawn out and badly written review!

All in all, the short stories collected in Miraculous Mysteries

were very consistent in quality. There were only two real stinkers,

Freeman (ripped off a well-known story) and Innes (completely

ridiculous), but skipped those two and that left only one (minor)

disappointment (i.e. Vivian). All of the other entries were either

decent, good or historically interesting. So no real complaints about

the overall quality of the collection.

However, it was a small let

down that this anthology did not collect any new sparkling classics

that were completely unknown to me, but that's the price one pays for

consuming ridiculous amounts of impossible crime-fiction. That being

said, this anthology is a welcome addition to the slowly growing row

of locked room themed short story collections of which there can

never, ever, be enough.

So,

despite my annoying nitpicking, I do hope this will not be the last

locked room anthology Edwards will compile for the British Library,

because I really do love impossible crime stories. And I'm only,

like, halfway through all of the novels and short stories listed by

Adey in Locked Room Murders.

I really, really need more anthologies to complete that task and reach full

enlightenment.

And, as always, I'll try to keep my next review a whole lot shorter.

I did not understand one of your comments. You stated that R. Austin Freeman ripped off a well-known story when he wrote The Aluminum Dagger. Since The Aluminum Dagger was written about 1909, I was wondering what that story was?

ReplyDeleteI certainly agree with your comment that the older mystery story writers had no problem incorporating new technology in their plots. Freeman and Arthur B. Reeve were particularly adept at this, but it was quite common, although you rarely see it now as far as I can tell. We should be in the middle of a new golden age of technologically themed mysteries; every issue of the scientific journals like Science or Nature contains the seeds of ideas for a dozen stories. The problem is that the modern authors have no real interest in telling stories.

I was referring to a 1903 short story by Conan Doyle, "The Empty House." The problem and solution from "The Aluminum Dagger" was, except for one detail, identical to the crime in Doyle's story. Only difference is that Freeman swapped a bullet for a light-weight dagger, but otherwise, the plot-idea was obviously lifted from "The Empty House." I expected so much more from Freeman.

DeleteYes, we could've been in a high-tech/science age of detective fiction, instead of a Renaissance Era, but we lost a generation or two of purely plot-oriented writers, who could have incorporated new innovations into classically-styled plots, when publishers shifted their focus to character-driven crime stories during the 1960s. So most of today's crime writers wouldn't know how to use, say DNA, to misdirect their reader (like a certain Japanese author did). Or even how to drop a good clue or two.

The Adventure of the Empty House hardly qualifies as a locked room mystery. Everyone knows at the start that the victim has been shot. It hardly takes a genius to figure out he was shot by a rifle. It is not playing the game to pull an air rifle from nowhere as the solution.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, Freeman's investigation is nothing short of brilliant, and this is probably his most frequently reprinted story, with good reason. A bullet could easily be fired from outside the room, but no one would expect that with a dagger, making it a true locked room mystery. Freeman's clueing in this regard is flawless. Thorndyke's crime scene analysis was far in advance of his time, and features of it were not common in real life for 15 or more years. Thorndyke uses both physical and psychological clues to draw up a profile of the murderer, something not all that common at this point. Freeman went so far as to test-fire a rifle he had modified himself to fire a dagger to prove to himself it could be done.

Freeman's explanation was as obvious, particular to modern readers, as Doyle's solution. The design and lightness of the dagger, in combination with the open window, should give you an idea how it was done. I was just really disappointed when I read the story for the first time and remember thinking how ridiculous similar the problem (and explanation) was to "The Empty House." So, I'm afraid we'll have to disagree about the merits of this one.

DeleteI, like you, have already read quite a few of these, and I'm disappointed to say that most of what remains doesn't really sound that compelling (I mean, when you're putting 'The Sands of Thyme' in your collection -- at the exclusion of almost anything else -- there's clearly something wrong going on...).

ReplyDeleteDisappointed to hear that the Vivan story doesn't even warrant a mention, as I have one of his novels and was hoping he'd be a genius of the genre -- though, sure, plenty of people wrote terrible short stories and great novels, and vice versa.

Still, that Sayers sounds interesting, and if it's thematically and tonally similar to Queer Complaints...well, colour me excited. So now I'm at a quandary: to buy or not to buy?

What really surprised me about the inclusion of "The Sands of Thyme," as well as the stories by Hodgson, Freeman and Olde, is that they can also be found in The Black Lizard Big Book of Locked Room Mysteries. And that anthology is, what, only two or three years old.

DeleteOn the other hand, I loved that this anthology gave me an opportunity to read the ones by Cumberland, Robbins, Sprigg, the Coles and Allingham. Not exactly stone cold classics, but I still liked them and loved re-reading the entries by Chesterton and Sayers.

You, as a fellow impossible crime fanatic, should read "The Haunted Policeman." No matter in what volume it is. Just read it.

Oh, and don't allow my disappointment over Vivian keep you from reading his novel. As you can see from my exchange with Anon about Freeman's story opinions can very much differ. Read and decide for yourself, is what I say!

Ha, fear ye not -- I shall be reading the Vivian...I've even bumped it up a few (theoretical, I'm not that organised) places. And, hell, at least we got an impossible crime anthology from one of the biggest-selling and most visible series out there at present, right?

DeleteI'm quite excited to see that there's also a collection of translated works coming in this series...some of them apparently first-timers in English. When you've got such a broad range of things to cover, and are doing as honest a job s these BL editions seem to be doing, I guess we should be thankful not to be overlooked. And, hey, maybe more will follow...with hopefully fewer, recently-collected stories, natch.

'The Haunted Policeman' has gone on my list. Wherever I read it, it shall be found...

You're not the only one who's excited about that forthcoming collection of translated work. Hopefully, the collection will include one or two impossible crime stories, which could easily be covered by the French and Japanese entries.

DeleteI'm also keeping my fingers crossed that the story representing my country will, at least, be half decent.

Yes, let's hope that the next locked room anthology from the British Library, if they decide to do another one, will have fewer familiar faces. And who knows, maybe John Sladek's "By an Unknown Hand" will finally get anthologized after four decades!

And good luck with hunting "The Haunted Policeman."

what is the "forthcoming collection of translated work" so i can put its name on my amazon wishlist? thank you

DeleteIt's titled Foreign Bodies.

Deletethank you. also i love your longer reviews.

DeleteYou're welcome and thanks! :)

DeleteReally glad this collection is out, and hope it will do wonders for locked room publications under the British library band.

ReplyDeleteI was also a bit miffed to it was Beware of the Trains that was chosen for Crispin. I was thinking that The Name on the Window would have also been a much much better entry. I think it was also in the Black Lizard collection as well. It's one of those annoying ones that people jump to even though it is not the best of the writers work, like The Invisible Man for example.

Crispin's "The Name on the Window" is a better locked room story than "Beware of the Trains," but I would have gone with one of the two impossible crime stories from Fen Country.

Delete"Death Behind Bars" is excellent and has never been collected anywhere else, while "A Country to Sell" is a good and somewhat technical locked room story that's virtually unknown. Even Adey overlooked it.

So you would be treating most readers to a story they likely have never read before. But who knows. Maybe they'll included in a future anthology.

Thanks for that very detailed breakdown TC - very much looking forward to getting this and seeing if we agree on it overall.

ReplyDeleteLooking forward to your take on these stories. Surely, we can always agree that are simply not enough of these kind of anthologies.

Delete