Last year, I reviewed the short story "Le mystére de la chambre verte" ("The Mystery of the Green Room," 1936) by Pierre Véry, "novelist of adventure, novelist of the fantastic," who believed in saving "what has been able to remain in us as the child that we were" ("...full of flaws, of changes of heart, of shadow and mystery") – essentially wrote fairy tales for grown-ups. One of his few works to be translated into English is L'assassinat du Pére Noël (The Murder of Father Christmas, 1934) and is a fine example of Véry's home blend of the formal, 1930s detective story with his brand of gentle surrealism.

I mentioned in the review that the few translations like the previously mentioned seasonal mystery novel and the now even rarer English edition of Le thé des vieilles dames (The Old Ladies' Tea Party, 1937) have since gone out-of-print. There seemed to be no plans or rumors swirling around at the time to translate Véry's other celebrated novels such as Le testament de Basil Crookes (The Testament of Basil Crookes, 1930) and Les quatre vipères (The Four Vipers, 1934). Little did I know that Crippen & Landru was putting the finishing touches to a brand new translation that was published back in December.

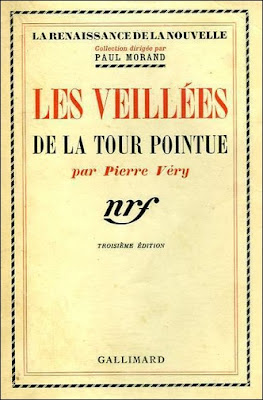

Renaissance man and author of Death and the Conjuror (2022), The Murder Wheel (2023) and the upcoming Cabaret Macabre (2024), Tom Mead, translated Véry's famous collection of short stories, Les veillées de la Tour Pointue (The Secret of the Pointed Tower, 1937) – which at the time caught the attention of Ellery Queen. This first English edition opens with a photocopy of a handwritten letter from Frederic Dannay to Véry thanking him for sending a copy of Les veillées de la Tour Pointue and hoped to see some of the short stories published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. Something that would not happen until "The Mystery of the Green Room" appeared in the August, 2011, issue of EQMM. More than sixty years after Dannay wrote the letter and now we have the whole collection.

In addition to translating this collection, Tom Mead penned insightful introduction that presented Pierre Véry as a writer who a "unique path" through the Golden Age of the French detective story. A mystery writer enjoying "the distinction of being both an exponent and a critic of the Golden Age" whose tales of mystery and imagination "often existed outside of the strict parameters of the conventional whodunit." Véry's mystery output consists of everything ranging from everything subversive reimaginings and parodies to the traditional locked room mystery, but always distinguishable by their "often-eccentric blending of genres" and his "taste for the surreal or fantastical."

Before

diving into this collection of short stories, I should note that the

Crippen & Landru edition neglected to list the original French

titles and publication dates. I found the original French titles, but

have no idea when, or where, they first published. So, lacking the

publication information, this one is going to be slightly less

autistic pedantic than most short story collection

reviews that can be found on this blog.

The Secret of the Pointed Tower begins with a short chapter, "A Message to the Reader," in which Pierre Véry himself is roaming the streets of nighttime Paris in search of somewhere, anywhere, to hang a man ("such is the morbid fate of mystery writers...") when he accidentally discovered a secret passage – revealing a dark, narrow passage. A passage leading to a hidden attic room in the pointed tower of the police headquarters, on the Quai des Orfevres, where he finds a pile of handwritten reports on "all kinds of crimes, burglaries, mysteries, enigmas." But written down as dry, clinical reports. These are full-fledged stories that Véry immediately began to copy to present to his audience under the title The Secret of the Pointed Tower. A near, simple little framing device to tie these vastly different stories together.

"Le menton d'Urbin" ("Urbin's Chin") is the first of these short stories following a so-called book-taker, "specialist in the theft of rare tomes," named Simonet. A bibliophile book-taker with designs on "a renowned collection of literary rarities" tucked away in the private library of a collector, Urbin. Simonet's carefully prepared burglary goes entirely wrong when coming across the bloodied, curled up remains of Urbin inside a crate, which is how the gardener finds him and the police believe him guilty. Simonet uses his imprisonment to work out whom of the potentially five suspects killed Urbin ("...by keeping quiet I might just be able to turn a decent profit out of this"). This is a fun little mystery caper and solid opening story that reads like a direct ancestor of the Bernie Rhodenbarr series by Lawrence Block. Loved it!

"Police

technique" (no translation needed) concerns the murder of Yvette

Lemoine and the

problem her death poses the police. Only person who

appears to have had the opportunity to deliver the fatal blows is her

cousin, Marcel, but he claims to be innocent and has no motive. Then

the police are called the bedside of Yvette who says with her dying

breath, "my uncles," but both men have "indisputable

alibis." Another possible interpretation of those dying words

implicates her fiancé, which again leads the police into a dead end.

It's not until Véry's lawyer and sometimes detective, Prosper

Lepicq, appears to confront the murderer that the case gets solved,

but not in the way Lepicq had hoped. I think this story is more

interesting for the style than the plot as it pulls a potential

locked room mystery, dying message, unbreakable alibis and even some

forensic shenanigans from the old bag of tricks – before ending as

a dark, psychological crime story. Lepicq actions at the end echoes

some of the practices of his American counterparts like Perry Mason

and John J. Malone.

"Police montée," translated here as "The Tale of a Tartlet," is one of my favorite stories from this collection. A charming, playful and excellent take on both the classical whodunit and inverted mysteries. Léon Petitquartier is the seventeen year old son of a pastry chef and an arachnid collector who had been given the unpleasant task of euthanizing the old family dog, Vega ("...the animal was quite literally dying on its feet"). Léon poisoned a honey tartlet with cyanide as a final meal for Vega, but, while being distracted for a few minutes, the poisoned tartlet disappears from the kitchen table. So now Léon has to wait nervously for the news to break that someone has been mysteriously poisoned, but the events doesn't quite play out like the teenager expected. This story really benefited from being longest story in the collection and particularly liked how the village community reacted to the news or simply the simple, but excellent, explanation to the whole mystery.

"La multiplication des négres," re-titled for this collection as "The Salvation of Maxim Zapyrov," tails a penniless Russian in Paris, "stumbling from weariness and weeping with hunger, desperate and begging," who believes a black policeman is hunting for him – which has to do with a "detestable thing" that happened in a dark, narrow street. Maxim Zapyrov tells his unusual story to a M. Paul. A crime story with a predictable twist and not really my poison, but not bad for what it is.

"Le prisonnier espagnol" ("The Spanish Prisoner") is modeled on the classic and titular confidence trick, which is still around today, but changed and adapted along with the times. You might know it as the Nigerian Prince email scam. In this story, the poor Celestin Lainé who surprisingly receives a letter from someone imprisoned in Spain and needs help to collect a trunk containing nearly two million francs. However, Lainé has four very rich friends and they decide to respond to the letter with somewhat predictable results. The key word there's somewhat, because the devil is always in the details and the end result is a good, solid and fun scam story. I love good scam story and the next one is even better.

"Les 700,000 radis roses" ("The 700,000 Pink Radishes") is not a locked room mystery or impossible crime, of any kind, but this story has a delightful, utterly bizarre plot and premise that will be appreciated by fans of John Dickson Carr and Paul Halter. The great Parisian publisher M. Hippolyte Gour keeps receiving a baffling, one-sided correspondence about the purchase of 700,000 pink radishes ("they are guaranteed fresh and free of worm bites") and an equal amount of radish leaves ("these will be dispatched to your personal address"). And, before long, his personal secretaries either get attacked or kidnapped. The case kicked up so much dust that it attracted "the attention of a band of popular mystery novelists" who "were trying to apply the method of their fictional detectives," but the problem of the 700,000 pink radishes seriously tasked their wits. Until they had their storybook moment, "where the police failed, the amateur sleuths succeeded," which comes with a small, delightful twist at the end. More importantly, this is one of those few detective story that manages to do something meaningful with a kidnapping plot (of sorts).

The next short story is "La soupe du pape" ("Soupe du Pape") and reads like Véry tried to recapture the magic of "Les 700,000 radis roses" without much success. A policeman finds a dozen pearls while shelling peas. So has to figure out where the pearls came from, how they ended up in his bag of peas and who stole them. This story did nothing for me.

The next two short stories are the previously mentioned "The Mystery of the Green Room" and "L'assassin" ("The Killer"), but have already reviewed the former (see link above) and the latter is a short-short barely covering two full pages. Fortunately, The Secret of the Pointed Tower concludes with an absolute banger!

"Cours d'instruction criminelle" ("A Lesson in Crime") is not really a mystery short story, but a science-fiction musing on the distant future, somewhere around the year 2500, where crime fiction "gradually took precedence over all other forms of literature" – until they all "fell into disrepute and then obscurity." In those future years, the great mystery writers of the early twentieth century have become the classics school children study from seventh grade onward. The study and history of the traditional detective story is central in every classroom ("if locked-room Y is shaped like an isosceles triangle ABC and locked-room Z is a hexagon MNOPQR, calculate...") and children ask their mothers how they would poison their dad or quiz their father on how he would snuff out his mistress! The ending is both humorous and very perceptive as it's something I can see happening under those circumstances, but Véry's vision of the year twenty-five hundred nonetheless feels like home. But I'm stuck with you lot. What can you do?

The Secret of the Pointed Tower ends with a parting message to the reader from Véry, "when I have more stories, you will be the first to know," but no idea if a second collection ever materialized. Tom Mead also included several pages of explanatory notes, which I always enjoy to find in translated mystery novels or collections.

So, all in all, the short stories collected in The Secret of the Pointed Tower perfectly demonstrates why Véry considered the detective story to be "the brother of the fairy tale." When blended with Véry's home brewed brand of surrealism, you don't always get the most orthodox or traditionally-styled detective stories. You can hardly call any of the short stories traditional, Golden Age-style mysteries, but that doesn't mean the quality isn't there. "The Tale of the Tartlet," "The 700,000 Pink Radishes," "The Mystery of the Green Room" and "A Lesson in Crime" are all first-rate for variously different reasons. "Urbin's Chin" and "The Spanish Prisoner" are simply good, solid stories. "Police Technique" is not quite as good, or solid, but interesting in how it played with different styles and tropes. Only "The Disappearance of Emmeline Poke," "The Salvation of Maxim Zapyrov" and "Soupe du Pape" were off the mark. Not much can be said about the two-page short-short. That's not a bad return for a collection as varied as The Secret of the Pointed Tower. More importantly, the fact that it was translated by Tom Mead is very hopeful for the future. John Pugmire is no longer alone in bringing these French-language novels and short stories to an international audience and the changes of getting a translation of Véry's legendary locked room mystery novel The Four Vipers sooner rather than later has gone up! In short, The Secret of the Pointed Tower is indeed something of a lost classic and comes highly recommended to fans of the short crime fiction.

Man, wish Crippen would release more of their books digitally. This seems interesting.

ReplyDeleteIt would be a good, cheap way to re-release some of the earlier, now out-of-print, collections like Brand's The Spotted Cat, Child's The Sleuth of Baghdad and Godfrey's The Newtonian Egg.

DeleteSounds good, but also unfortunately a little out of my wheelhouse! Still very happy to see others getting into the translation game.

ReplyDeleteI have this Pierre Véry collection on the big pile but have yet to read it. What I did do is track down his book, "The Old Ladies' Tea Party" that you mention in your post and I am glad I did. It certainly was different from my typical GAD reading with all the typical surreal characteristics of Véry's writing.

ReplyDeleteThe characters were truly bizarre including a well-dressed, educated dwarf who marches up and down the village streets, a woman who dresses up each night in her own fantasy world, a man and a woman communicating with each other via coded messages, two spinster sisters who wear only black for decades, a group of elderly women with a fascination with all forms of the occult, etc.

The narrative is unstructured, is at times difficult to follow and reads like an outlandish adult fairy tale.

So whilst I won't seek out much more his work, I enjoyed this as a palate refresher for my GAD reading. It does offer a strong puzzle (albeit one that is only vaguely clued) and finishes strongly with the confrontation of the killer.

"The narrative is unstructured, is at times difficult to follow and reads like an outlandish adult fairy tale."

DeleteThat describes his fiction to a T and you can more or less expect the same from The Murder of Father Christmas with the short stories having clearer focus and structure, due to their shorter length (obviously). So see what you make of it and, above all, enjoy the collection!

Fingers still crossed for a translation of Véry's The Four Vipers!

I just finished "The Secret of the Pointed Tower" and enjoyed several the stories. "The Tale of the Tartlet", "The Spanish Prisoner" and "The 700,000 Pink Radishes" are all good fun.

ReplyDeleteGAD novels and stories all have varying bits of fantasy about them. Pierre Véry's stories are a pleasantly extreme example of this (e.g., his odd characters include a man with donkey shaped chin, one with a head like a fist, another who collects spiders, etc.). So again I recommend Véry for anyone who wants a change of pace from his/her GAD reading.

I continue to be impressed with the Crippen & Landru collections and am now off to buy their latest offering Tom Mead short stories including several with his magician detective, Joseph Spector.

Glad you enjoyed it. You're right Véry is a perfect change of pace. Maybe even an acquired taste like Gladys Mitchell. Here's to more in the future! I'm also looking forward to the Tom Mead collection. Mead's short stories sound fascinating, but they're scattered all over the place. So it's nice to have his short stories, up till now, in a single volume. It also gives me hope Crippen & Landru might do a Paul Halter collection or a follow up The Realm of the Impossible.

Delete