"Everything has a beginning and an end. Life is just a cycle of starts and stops. There are ends we don't desire, but they're inevitable, we have to face them. It's what being human is all about."- Jet Black (Cowboy Bebop)

First of

all, I want to beg your forgiveness for indulging, three times in the span of

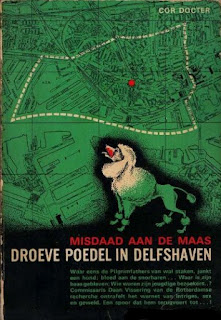

four weeks, in those pesky, untranslated detective stories, but Cor Docter has

captured my fascination and this review will round out the trilogy of books

featuring Commissioner Daan Vissering – a kind and intelligent policeman. Even

more good news, I have in my possession a little known, disregarded locked room

mystery from the 1930s and it's up next, but for the time being, bear with me

as I babble about one more of these books.

Now that

I have read all three volumes in this series, I understand what Docter set-out

to do with them and it's an effort that I very much appreciate: Droeve poedel in Delfshaven (Melancholic Poodle in Delfshaven, 1970) was a

Grand Whodunit in the tradition of Agatha Christie, Koude vrouw in Kralingen

(Cold Woman in Kralingen, 1970) re-opened John Dickson Carr's beloved

Locked Room Mystery for business and Rein geheim op rijksweg 13 (Pure

Secrecy on Highway 13, 1971) mimics the signature trademark of Ellery Queen, the Dying Message. However, as mentioned before in these reviews, they're

hardly throwbacks, but more of an overhaul that resettles them in the modern world

of the early 1970s – populated with mostly working and lower class people who are

caught in the meshes of intrigue.

Highway

13 was one of the busiest highways of the country and there’s always someone

traveling down that road, no matter what hour of the day it is, which makes the

plan of two petty thieves, Sander Wils and Peter Ruivenvoorde, all the more audacious.

They want to strip a delivery van, abandoned on the emergency lane, of its valuable

parts, but what they find in the back of the car throws a spoke in their wheels:

slumped between scattered protest signs there’s the body of a man, hit over the

head, and one hand resting in an open canister of red paint. On the inside of

the van the dying man had scrawled "16NK2-" and it’s definitely a sign that

Vissering's plan for Charles Dickens-style Christmas is in jeopardy. The scene

of the crime also provided me with the post title, because the stranded van,

containing the dead man's message, reminded me of a bottle that had just

drifted on shore after an exhausting journey – with the lights and sound of passing

cars standing in for the murmur of the sea and a cone of light from a nearby lighthouse. I thought it was an interesting image.

The thorough investigation of Vissering and his men uncover a number

of plot threads that run in various directions, but still appear to be connected to

the body in the van. There are the signs protesting the pollution of the air

with garish slogans and this turns up a second death, a suicide of the wife of

one of the members of a protest group, and a glass of diluted bleach is one of the key clues

in this little side puzzle. You need a piece of trivial, household

knowledge from this particular period to completely solve it, but it's actually

quite clever and could've easily been used to give a satisfying explanation to a

locked room scenario that turns out to be nothing more than a simple suicide. Docter

only had to let Ella van der Klup jump from an open window inside her locked

apartment, instead from the gallery outside, with her husband snoozing in the

other room.

Vissering

also has to tangle with "Boere-Bram," a Lombard, of sorts, of scrap metal and

junk, who has a link with the murdered man, who turns out to be the straight up

brother of a convicted criminal who has stashed away his loot, hundred fifty

thousand guilders, as a nest egg for when he gets out – which is sooner than

everyone expected! There’s also an old, mysterious man, named Siem Bijl,

bumping into Vissering wherever the investigation takes him and a German

bayonet is also thrust into the case. As to be expected by now, Docter pulls

off a conclusion as classical as it's satisfying. It's like the back blurb

said, "This time no Carter Dickson effects, but 'keys' that are reminiscent of

the best plots of Ellery Queen, Peter Quentin (sic) or the immortal

Dorothy Sayers.”

Lastly, I

should mention that Pure Secrecy is also very strong in its commentary on

modern society and its condemnation of the annexation of Overschie by Rotterdam

– polluted and defaced in the process. Highway 13 was carved right through it and "housing barracks" (i.e. flats) tore the old atmosphere and community asunder. Docter

already warned and apologized in his introduction that his description of the

then present-day Overschie would be a very colored one – because the old

Overschie was very dear to his heart.

Docter's detective

novels may be steeped in old traditions, but he made a valiant effort at updating

them to modern times and, more often than not, succeeded in doing so and this earned

himself a place among the ranks of post-GAD writers who proved the old adage

that a classic never goes out of style.