"I've always wanted to make the world a more rational place. I'm still working on it."- Penn Jillette

It's impossible to pinpoint how many

detective stories and novels were written since Edgar Allan Poe's 1841

inaugural locked room mystery, "The Murders in the Rue Morgue," that contains

an impossible crime plot, but the revised edition of Robert Adey's Locked

Room Murders and Other Impossible Crimes (1991) managed to gather over two

thousand titles – an impressive number, to be sure. Until you realize it was

even then an incomplete, and by now outdated, list of stories originally

published in English with a few foreign titles tucked away at the end.

The trope still makes a regular

appearance in contemporary crime fiction, but the casual mystery reader (and

publishers) still appears to be incapable of identifying or differentiating it

from other sub-genres. I've seen Jonathan Creek being described as a

supernatural cop show, conjuring up a picture of modern day Thomas Carnacki

stalking the moonlit churchyards for preternatural shadows, while Agatha Christie is dragged in by hair as the most famous practitioner of the "Locked

Room Mystery" whenever a writer takes a stab at the "Closed Circle of Suspects"

situation by setting their story in an isolated location. If only John Dickson Carr had written Merrivale's Christmas, the best of the Drawing Room

Mysteries from the 1930s, we would now probably be looking forward to John

Cleese's final performance as H.M. in a TV adaptation of The Cavalier's Cup

(1953).

So I'll be climbing atop my hobbyhorse in

an attempt to delineate the "Locked Room Mystery," and because fans like to

ride their hobbyhorse and rattle on as they pretend to be giving an actual

lecture.

The Locked Room

A room with the door and windows locked

and latched from the inside, even dead bolted or sporting steel shuttered or

barred windows, containing a victim who clearly died at the hands of someone

else – who’s not found within the confines of that space. The question that has

to be answered is how the murderer escapes from the scene of the crime without

resorting to cheap trickery or the supernatural.

Many of Poe's successors were,

retrospectively, guilty of emptying out the entire bag of cheap tricks before

the end of the 19th century rolled around: horrifying mechanical contraptions,

terrifying natural phenomenon, hidden passageways, unknown poisons and venomous

creatures explores plucked from previously unexplored regions of the globe.

L.T. Meade and Robert Eustace's A Master of Mysteries (1898) therefore

feels like a goodbye to that particular era, in which a professional "Ghost

Breaker," John Bell, rationalizes such peculiarities as a room that kills and a

talking statue in what essentially is also one of the first collection of short

impossible crime stories. The timing was also perfect for a final bow in lieu

of Israel Zangwill's landmark novella, The Big Bow Mystery (1894), which

moved away from murderous beasts and obscure poisons in order to play with the

readers assumptions – a method adopted in Gaston Leroux's influential Le

Mystère de la chambre jaune (The Mystery of the Yellow Room, 1907)

and G.K. Chesterton's compendium of Golden Age plots The Innocence of Father Brown (1910).

The physical approach to bridge the gap

between the impossible-and impossible was not ditched by the side of the road

except for the huge human crushing devices and focused more on fiddling with

locks, prepping windows and roofs or string everyone along with some wire or a

pole. Of course, these are only the basic methods and one favored by today's

crop of mystery writers who dabble in them. Good, classic examples of these

physical approaches to create the impossible are S.S. van Dine's most readable

Philo Vance mystery, The Kennel Murder Case (1933) and Clyde B. Clason's

The Man from Tibet (1938).

At the dawn of the Golden Age, the trick

of locking a box from the inside evolved along the lines set out by Zangwill,

Leroux and Chesterton by playing with their readers assumptions of time, place

and even everyday objects as demonstrated in the Father Brown story "The Hammer

of God," in which a man's head is shattered to pieces from a single blow from a

tiny hammer and the strength involved makes the blacksmith a logical suspect.

He's the only one who could've done it. Until Chesterton shows you how

everyone, regardless of their physical strength, can yield a tiny hammer with

obliterating force and the one (im) possible suspect also found its way into the

locked room.

The suspect is discovered alongside the

victim inside a room sealed from the inside and/or watched/guarded from the

outside and this person appears the only person who could’ve committed the

murder – and it's up to the detective to prove otherwise.

Carter Dickson's The Judas Window

(1938) is the most well-known example, in which Sir Henry Merrivale makes his

only appearance in his capacity as a barrister to defend Jimmy Answell from

stabbing his prospective father-in-law to death with an arrow while alone with

him in his hermitically sealed study. H.M. insists that the real murderer

aggressed the room through a Judas window and "there's one in every room."

Bill Pronzini explored this premise in Hoodwink (1981) as the Nameless

Detective has to bail out an old pulp writer, who has fallen on hard times and

was found hovering above a body with a gun after a shot was heard behind the

locked door of his hotel room. Giant of the Short Stories, Edward D. Hoch, came

up with a solution for "The Leopold Locked Room" as staggering as the situation

he put Captain Leopold in: locked with his ex-wife in a room when she suddenly

drops dead from a bullet discharged from his gun that he had not pulled from

his holster. Robert van Gulik's "The Red Tape Murders," collected in Judge

Dee at Work (1967), is perhaps the only trick in the locked room genre that

manages to be utterly ridiculous and fairly plausible at the same time as Dee

becomes involved with an assassination at a military fortress in the year 663.

They've a suspect in custody, but questions have been raised about his guilt

and Dee's absurd solution turns the military complex setting into a

surrealistic painting by Salvador Dali as your brain is turning the words into

mental images. In stark contrast stands Helen Reilly's Dead Man Control

(1936), an early American police procedural about a young bride found

unconscious next to her slain husband in their locked study with a gun in hand,

but the whole story was only slightly more exciting than a bout with insomnia.

Carter Dickson's The Judas Window

(1938) is the most well-known example, in which Sir Henry Merrivale makes his

only appearance in his capacity as a barrister to defend Jimmy Answell from

stabbing his prospective father-in-law to death with an arrow while alone with

him in his hermitically sealed study. H.M. insists that the real murderer

aggressed the room through a Judas window and "there's one in every room."

Bill Pronzini explored this premise in Hoodwink (1981) as the Nameless

Detective has to bail out an old pulp writer, who has fallen on hard times and

was found hovering above a body with a gun after a shot was heard behind the

locked door of his hotel room. Giant of the Short Stories, Edward D. Hoch, came

up with a solution for "The Leopold Locked Room" as staggering as the situation

he put Captain Leopold in: locked with his ex-wife in a room when she suddenly

drops dead from a bullet discharged from his gun that he had not pulled from

his holster. Robert van Gulik's "The Red Tape Murders," collected in Judge

Dee at Work (1967), is perhaps the only trick in the locked room genre that

manages to be utterly ridiculous and fairly plausible at the same time as Dee

becomes involved with an assassination at a military fortress in the year 663.

They've a suspect in custody, but questions have been raised about his guilt

and Dee's absurd solution turns the military complex setting into a

surrealistic painting by Salvador Dali as your brain is turning the words into

mental images. In stark contrast stands Helen Reilly's Dead Man Control

(1936), an early American police procedural about a young bride found

unconscious next to her slain husband in their locked study with a gun in hand,

but the whole story was only slightly more exciting than a bout with insomnia.

The biggest no-no for the

one-possible-suspect scenario is if that suspect is innocent and not offered as

a surprise twist that renders the whole locked room pointless. A cop-out as

condemnable as having the victim designing his death to look like a murder and

it guarantees disappointment, because readers expect something from an

impossible crime. You can't say you're going to pull a bunny from a top hat,

whisk out a sock puppet and expect to get away with it. It's a trick. We get

it. But if you promise a bunny (i.e. a locked room) you have to deliver a

bunny.

Wide Open Spaces

You'd think wide open spaces would afford

more security in a detective story, because snipers and knife-throwers are a

rare sight, even there, but there are more than enough stories in which people

are knifed, bludgeoned or pushed to their deaths in front of witnesses by

invisible entities – making them almost borderline horror novels, if you add

the suggestion of the supernatural to the mix.

Carter Dickson's The Unicorn Murders

(1935) is a successful collision of universes as the formal detective story and

the spy thriller are thrown into a French château alongside the

passengers of a stranded airplane, a master criminal, spies and an invisible

unicorn roaming the hallways as it gores several people in front of

eyewitnesses. Under his own name, Carr mixed spies and adventure again in his

historical novel Captain Cut-Throat (1955) that also includes a series

of stabbings of Napoleon's sentries in front of witnesses without any of them

having seen the perpetrator. Yet another known example from Carr, "The Silver

Curtain," collected in The Department of Queer Complaints (1940), gives

another example of an invisible assailant striking this time in a cul-de-sac –

leaving onlookers baffled.

But the Grandmaster of the Locked Room

Mystery was not the only writer who produced noteworthy mysteries of this type.

The pages of Anthony Wynne's The Silver Scale Mystery (1931)

accommodates no less than three impossible crimes, two of them committed in

locked or watched rooms, but the third was done outside in front of a witness

and the only thing that was seen was the gleam of a weapon. A year later W.

Shepard Pleasants sole mystery novel, The Stingaree Murders (1932), was

published, and likewise, contained three seemingly impossible crimes and two of

them fit the description of the invisible assailant: a man is stabbed while

fishing alone in a skiff and an unseen force drags another from the deck into

the water and drowns him. These are not well-known mysteries, but well-worth

checking out for their original contributions.

Naturally, these open spaces with

witnesses is a perfect conditions for a murder during a stage performance with

Christianna Brand's Death of Jezebel (1948) and Ngaio Marsh's Off With His Head (1957) being the most well known classical examples. During

the 1980s, however, these open-air, theatrical locked rooms became the

specialty of Herbert Resnicow and nobody did them better. Nobody! The Gold Curse (1986) is perhaps the most conventional one in setting and execution

as one of the actresses in Rigoletto is fatally stabbed during the final

act of the play, but The Gold Deadline (1984) is the most ingenious one

of them all – involving another stabbing during a ballet performance of the

troupe’s manager in an inaccessible box seat shared with the detectives of the

story! The solution may raise some eyebrows, but Resnicow does provide a motive

why anyone would go through such insane and risky length to commit a murder

under those conditions. Resnicow showcased his background as a civil engineer

and using his knowledge to create locked room illusions on a architectural

level like in his other masterpiece, The Dead Room (1987), in which the

scene of the crime is a guarded, multi-level archaic chamber of a company

producing audio equipment and delivers a tailor-made answer that only works in

that particular room.

One more example worthy to mention here

is Paul Halter's Le Diable de Dartmoor (The Demon of Dartmoor,

1993), set in the desolate landscape of Conan Doyle's The Hound of the

Baskervilles (1902), in which malicious, but invisible, entity is throwing

local girls from a granite spur or from an open window.

No Footprints

Arguably the hardest of all impossibilities

to pull off is figuring out how someone was killed at close range while

standing in the middle of a field of virgin snow, unbroken mud or wet sand –

and only the victim's foot prints lead up to the body. A variation on this

theme is a house surrounded with unscathed snow or mud.

John Dickson Carr himself produced only

original and really good example in She Died a Lady (1943), written

under the Carter Dickson byline, set during those dark days of WWII in which

two lovers decide to jump off a cliff together, but they were shot when they

were standing at the edge of the cliff. The murderer must have hovered in

mid-air, because the only footprints in the sand belonged to the victims! In my

opinion, She Died a Lady was Carr's most successful treatment of the

no-footprints variety for the simple reason that it was a new idea in a book

that was also one of the authors' best attempts at writing a crime novel.

One of Carr's imitators, Herbert Brean,

wrote a rather famous book among impossible crime enthusiasts, Wilders Walk

Away (1948), about a town dating back to the Pre-Civil War era and some

members of the town's leading family don’t die – they simply fade away. One of

the impossible disappearances happens on a stretch of beach where the footprints

simply stop. Unfortunately, the second part fell a bit flat after the first and

the solutions were tad bit disappointing, to be honest. The anime series Tantei Gakuen Q used the framework of this novel for The Kamikakushi Village

Murder Case (episodes 16-21), but the impossible crimes were much better

done.

One of Carr's imitators, Herbert Brean,

wrote a rather famous book among impossible crime enthusiasts, Wilders Walk

Away (1948), about a town dating back to the Pre-Civil War era and some

members of the town's leading family don’t die – they simply fade away. One of

the impossible disappearances happens on a stretch of beach where the footprints

simply stop. Unfortunately, the second part fell a bit flat after the first and

the solutions were tad bit disappointing, to be honest. The anime series Tantei Gakuen Q used the framework of this novel for The Kamikakushi Village

Murder Case (episodes 16-21), but the impossible crimes were much better

done.

My favorite "no-footprints" are a short

story by Arthur Porges, "No Killer Has Wings," in which Dr. Joel Hoffman has to

figure out how a man was clubbed to the death on a beach covered with only foot-and

paw prints of the victim and his dog. The solution is a gem! The Jonathan

Creek television special, The Black Canary (1998), is another

personal favorite that unfolds in your living room like a dramatized stage

illusion as you try to figure out how the limping man in rags could've trudged

through several inches of snow and leave a blanket of unbroken snow behind him.

There are many variations on the

impossibility of footprints as William DeAndrea demonstrated in Killed on the Rocks (1990), when he deposited a recently murdered person on the

titular, white-capped rocks – encompassed by a blanket of pristine snow.

Clayton Rawson had yet another approach in the self explanatorily titled book The

Footprints on the Ceiling (1939), but revisited the premise in a short

story, "Nothing is Impossible," in which paw-prints of a two-feet, three-toed

alien creature are found on the dusty surface of a filing cabinet in the office

of a murdered UFO investigator. Rawson's ideas were interesting experiments

that were, alas, not good enough to become master copies, but interesting ideas

nonetheless.

Spirited Away

In an ironic twist worthy of the best

Golden Age mysteries, the most famous disappearance mysteries of all is lost if

self, or rather, it doesn't really exist. Dr. Watson mentioned in "The Problem

of Thor Bridge," from The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes (1922), that among

his "unfinished tales is that of Mr. James Phillimore, who, stepping back

into his own home to get his umbrella, was never seen more in this world."

Doyle never implied there was anything impossible about Phillimore’s

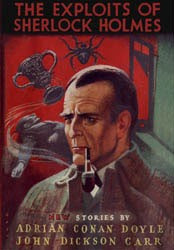

disappearance, but this single reference spawned many pastiches. Adrian Conan

Doyle and John Dickson Carr co-wrote a semi-official continuation of the canon

with The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes (1954), which touched upon this

problem in "The Adventure of the Highgate Miracle" and has Carr's fingerprints

all over it.

In an ironic twist worthy of the best

Golden Age mysteries, the most famous disappearance mysteries of all is lost if

self, or rather, it doesn't really exist. Dr. Watson mentioned in "The Problem

of Thor Bridge," from The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes (1922), that among

his "unfinished tales is that of Mr. James Phillimore, who, stepping back

into his own home to get his umbrella, was never seen more in this world."

Doyle never implied there was anything impossible about Phillimore’s

disappearance, but this single reference spawned many pastiches. Adrian Conan

Doyle and John Dickson Carr co-wrote a semi-official continuation of the canon

with The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes (1954), which touched upon this

problem in "The Adventure of the Highgate Miracle" and has Carr's fingerprints

all over it.

"The Long Way Down" is a one-off by Ed

Hoch, who apparently had grown bored with snatching people away from sealed rooms

or under the noses of baffled onlookers, and decided to challenge himself: how

do you explain a man falling from a top-floor window of a skyscraper and

vanishes in mid-air – only to hit the pavement a few hours later? Hoch handled

the explanation with the routine of seasoned magician. Slightly more fantastic

is "The Glass Bridge," a story from Robert Arthur's Mystery and More Mystery

(1966), in which a venerable mystery writer spirits a blackmailer from his home

encircled with unbroken snow indicating that she never left the premise. The

mystery is how the murderer made blackmailer disappear when his fragile

condition does not allow him to have buried or chopped up the body. A

shamefully under appreciated story, IMHO.

Sometimes a disappearance appears impossible,

because that what dematerialized is so big that it couldn't have happened. The

novella "The Lamp of God," collected in The New Adventures of Ellery Queen

(1940), and Edmund Crispin's The Moving Toyshop (1946) are the most well

known examples in which respectively an entire house and toyshop vanish over

night. Trains vanish into thin air in Conan Doyle's "The Lost Special" and

Ellery Queen's "Snowball in July." Hugh Pentecost's "The Day the Children Vanished" has a school bus driving into a dugway and never have them emerge

from the other end.

Weapons also have a tendency to fade out

of existence after a crime had been committed, but scene had been secured and

guarded with nothing turning up on the subsequent search of the place or the

suspects. Ellery Queen's The American Gun Mystery (1933) deals with the

shooting of a rodeo rider witnessed by twenty thousand witnesses who saw

nothing and the murder weapon appears not to exist. I've always thought this

could've been one of the classics were it not that the story shot itself in the

foot with an utterly ridiculous solution. The Man With Bated Breath (1934)

by Joseph B. Carr had a far more successful way to make gun vanish from a secured

premise where four people were just shot and alternative, pot-smoke take on John

Dickson Carr. Speaking of the master, I think he came up with the best and most

elegant solution in "Inspector Silence Takes the Air," a stage-play from 13 to the Gallows (2008), set in a radio studio interrupted by an on-air shooting

and an air raid – with the firearm nowhere to be found in that small studio. Blind Drifts (1937) by Clyde B. Clason also deserves a mention for the tantalizing

side puzzle of a gun that seems to have dissolved after an attempted murder in a

mineshaft.

Miscellaneous Impossibilities

Of course, these are only basic and

popular models of the impossible crime, but everything qualifies as long as its

manifestation appears to be breaking the laws of nature and are fairly

explained. About the Murder of a Startled Lady (1935) by Anthony Abbot

has a spiritualistic medium who claims to be channeling the spirit of an unknown

and murdered woman, which leads to a terrifying discovery. Not as good as the

spiritualist circle found in John Sladek's Black Aura (1974), who

disappear from locked lavatories or plunge to their death after levitating in

mid-air and stands with the best impossible crime novels from more noted

writers. Joseph Commings had one of the more versatile minds when it came to

coming up with new angles to the locked room and bumped off divers while alone

in a ship wreck, impaled people on swords that could've only been wielded by

giants, ghostly finger prints and even a dome-shaped room made of glass where a

murderer managed to escape from. The lion's share of these stories can be found

in Banner Deadlines: The Impossible Files of Senator Brooks U. Banner

(2004).

There are also eerily predictive dreams (Agatha

Christie's "The Dream," Paul Halter's "The Cleaver" and the Jonathan Creek

episode The Eyes of Tiresias, 1999), otherworldly creatures praying on

humans (Hake Talbot's Rim of the Pit (1944), Mack Reynolds' The Case

of the Little Green Men (1951), and America's answer to Christianna Brand,

Helen McCloy's Through a Glass, Darkly, 1950) or people who refuse to die

(Herbert Brean’s The Traces of Brillhart, 1961), and many, many more

variations like SF and fantasy hybrids and locked room capers. But there always

has to be a sane, rational explanation that's preferably clever and played fair

with the reader.

Links:

My Favorite Locked Room Mysteries I: The Novels

My Favorite Locked Room Mysteries II: Short Stories and Novellas

Just About as Strange as Fiction: Day to Day Miracles (real-life locked room mysteries, part I)

Out of the Tidy, Clipped Maze of Fiction (real-life locked room mysteries, part II)

When Oddities of Fiction Encroach on Reality (real-life locked room mysteries, part III)

Sealed Rooms and Ghoulish Laughter: Tributes to John Dickson Carr

A List of Dutch Impossible Crime Novels

Amazing pst TC - that should keep everyone who loves impossible mysteruies going for the rest of the year at least!

ReplyDeleteThat should say 'post', rather than omething a bit rude that sounds a bit like post ...

ReplyDeleteThanks Sergio! And I think my taste and opinions can be considered "pesky," if someone happened to be an exclusive reader of noir or literary thrillers. Lets just say you gallantly voiced an opinion that isn't often aired on this blog instead of making a typo. ;)

DeleteEh, wha... *sigh* Misusing 'locked room' for 'closed circle' is just something I'll never understand =_=

ReplyDelete(Unlike the term 'inverted mystery' by the way. At least you could argue that it actually isn't inverted, chronologically speaking)

The only "inverted mystery," chronologically speaking, I can think of is Pick Your Victim by Pat McGerr, but I guess it's just easier to say/write than “how-to-catch-'ems.”

Delete