"You're always hearin' that things were better in the good ol'

days... I'll tell you one thing that was better—the mysteries. The real

honest-to-goodness mysteries that happened to ordinary folks like you an' me.

I've read lots of mystery stories in my time, but there's never been anything

to compare with some of the things I experienced personally."

- Dr. Sam Hawthorne (Edward D. Hoch's "The Problem of the Covered Bridge,"

from Diagnosis Impossible: The Problems of Dr. Sam Hawthorne, 1996)

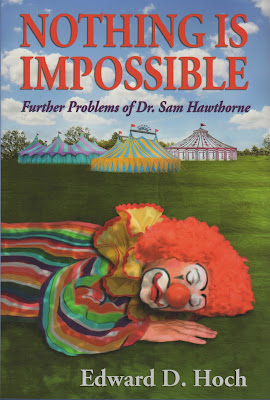

Edward

D. Hoch was a giant in the field of short form mysteries, having written

roughly nine hundred detective stories since his literary career began in 1955,

which were published in such famous periodicals as Ellery Queen's Mystery

Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine – spawning a sundry

cast of series-characters in the process. I know that I'm perhaps slightly

biased, but my favorite of Hoch's creations is unquestionably Dr. Sam

Hawthorne.

Dr. Sam Hawthorne was a physician in the

fictitious New England town of Northmont, but stories are his reminiscences, as

an older man, on a period that stretched across three decades. The first story

in the series, "The Problem of the Covered Bridge," was published in 1974 and

took place in March of 1922, while the final one, "The Problem of the Secret

Patient," appeared in 2008 and was set in October, 1944. It's an unusual series

in that the stories and characters are not frozen in time, which tends to

happen with long-running series.

Dr. Sam Hawthorne was a physician in the

fictitious New England town of Northmont, but stories are his reminiscences, as

an older man, on a period that stretched across three decades. The first story

in the series, "The Problem of the Covered Bridge," was published in 1974 and

took place in March of 1922, while the final one, "The Problem of the Secret

Patient," appeared in 2008 and was set in October, 1944. It's an unusual series

in that the stories and characters are not frozen in time, which tends to

happen with long-running series.

Time passes at a normal rate in the small

town and the people who live there, such as the (semi-) regular characters, are

not unaffected by the tick-tock of the clock, but there's one element that's

constant and insists on returning with the same regularity as the seasons –

namely the locked room murders and other seemingly impossible problems!

Northmont has an average homicide rate

that dwarfs Jessica

Fletcher's Cabot Cove, but crimes in the former insist on defying the laws

of reality: a horse-and-buggy inexplicably vanishes from a covered bridge, a

man is strangled by the branches of a haunted tree, a murder is committed in a

locked, octagon-shaped room and a solo-pilot is stabbed in mid-air inside a

locked cockpit. These are merely a handful of examples from the first two

collections of excellent stories, Diagnoses

Impossible: The Problems of Dr. Sam Hawthorne (1996) and More

Things Impossible: The Second Casebook of Dr. Sam Hawthorne (2006), but

this review will concern itself with the third volume of stories, which is

titled Nothing is Impossible: Further Problems of Dr. Sam Hawthorne

(2014).

However, before I take a look at the

individual stories, I have to make a note here and say that the collection, as

a whole, was not as strong as its predecessors. Somehow, the stories lacked

that magical touch or failed to live up to their own premise, which really

surprised me. Hoch was known for consistency in quality, but that was not on

display in this collection. Don't get me wrong: there were a couple of good

stories, but none of them as original ("The Problem of the Pink Post Office")

or classical ("The Problem of the Octagon Room") as some of the tales gathered

in the previous volumes – which really is a pity. Now that I have dampened your

spirits and enthusiasm... lets take a look at the stories!

"The Problem of the Graveyard Picnic" was

published in the pages of EQMM in June 1984 and takes place in the

Spring of 1932. Dr. Sam Hawthorne is moving from his small office in the center

of town to a remodeled wing of Pilgrim Memorial Hospital, which is being

downsized after the eighty-bed facility had "proven far too large for the

town's need." In between moving and seeing patients, Hawthorne pops outside

to attend the funeral of a prominent citizen in the cemetery in front of the

hospital and comes across a picnicking couple, but the woman gets up and runs

away when she sees the doctor – witnesses how an invisible force pushes her

over a stone-railing of a swollen creek. A nice, fun little story, but I

figured how it was done while the crime was in progress.

|

| The first collection of Dr. Hawthorne stories |

"The Problem of the Crying Room" appeared

in November 1984 issue of EQMM and the story happens in June of 1932.

Northmont is in the midst of the centennial celebration and the high point of

the festivities is the opening of the town's very first talking-picture palace.

The Northmont Cinema is equipped with a glassed-in, soundproof room for

families with babies or small children, called a "Crying Room," but the small

room attracts the attention of Sheriff Lens and Dr. Hawthorne when the

projectionist commits suicide – leaving a note behind confessing to the locked

room murder of Mayor Trenton on opening night. However, the opening night is

not until the following night!

Mayor Trenton insists on watching part of

the movie from the soundproof room, because the would-be assassin is dead, but

a single gunshot goes off and wounds the Mayor. Dr. Hawthorne was with him

inside the room and Sheriff Lens was guarding the only door, but all of those

precautions failed to stop an aspiring assassin from taking a shot at the

prospective victim. I loved the premise and the ideas Hoch was working with,

but the solution seemed to lack that magical touch of ingenuity and I'm afraid

there might be some medical objections to the method – such as the tendency of

blood to coagulate. I still tend to like this story though.

"The Problem of the Fatal Fireworks" was

first published a May 1985 issue of EQMM and takes place on the 4th of

July of the same year as the previous story. It's also the first really

disappointing story from this collection. The elements that were carried over

from the previous story were nice and the whodunit-aspect was decent, but the

question regarding how "half a stick of dynamite" was inserted into a

sealed package of harmless firecrackers was hardly worth the label of an

impossible crime.

"The Problem of the Unfinished Painting"

was published in EQMM in February 1986 and takes place in the Fall of

1932. A very rewarding story, because it showed a negative side effect to

playing amateur detective. Dr. Hawthorne is asked by Sheriff Lens to assist in

the locked room murder of Tess Wainwright. She was found slumped in a chair at

her easel, strangled to death with a long paint-spattered cloth, but all of the

windows were latched from the inside and the cleaning lady was in sight of the

only door to the studio – which she claimed was closed the entire time she was

there. The fun part of the plot is that the murderer was attempting to hammer

out a ironclad alibi, but unforeseen circumstances transformed into a "closed-room

situation" and that ruined everything. However, while he was out playing

detective something happened at the hospital that makes Dr. Hawthorne decide to

devote his full attention to his patients.

"The Problem of the Sealed Bottle" was

published in EQMM in May 1986 and the story takes place on December 5,

1933, which was the period when Franklin D. Roosevelt had been elected

President of the United States and delivered on his promise to repeal

Prohibition. Slowly, the US is being stocked, legally, with booze and Northmont

is no exception, but the first bottle of spirits to be (legally) unsealed

contained a potassium cyanide. I thought the background of the story, death of

an era, was more interesting than the plot itself.

"The Problem of the Invisible Acrobat" first appeared in the December 1986 issue of EQMM and takes place before the

events from the previous story, during the summer of 1933, when the circus came

to Northmont. The story has one of the better impossible problems collected in

this volume of stories. Dr. Hawthorne takes Sheriff Lens' nephew, Teddy, to the

circus where the death-defying stunts of the five Lampizi Brothers are part of

the main attraction, but one of the them vanishes in mid-air and only leaves

behind an empty trapeze – "swinging back and forth" as if "supporting

the weight of an invisible acrobat." The explanation for the vanished

trapeze-artist is clever without being incomprehensible, a semi-sentient being

should figure out the main gist of the trick, but the vanishing is tied-in with

a second plot-thread involving the body of clown covered in stab wounds. I

expected more of these type of stories from Hoch in this collection.

|

| The second collection Dr. Hawthorne stories |

"The Problem of the Curing Barn"

originally appeared in EQMM in September 1987 and takes place in

September 1934. A wealthy business tycoon, Jasper Jennings, who came to

Northmont during the depths of the Depression to grow tobacco, but he soon was

murdered after the first harvest – a straight-razor slashed across his throat

in a dark barn where the plants are being air-cured. Sheriff Lens is glad that

it's "not one of those locked-room murders," because barn has "more

holes than a rusty sieve," but there was no opportunity to get rid of the

murder weapon. I've seen the explanation for the vanishing murder weapon before

in stories, but they post-date this one and wonder if the trick originated in

this tale.

"The Problem of the Snowbound Cabin" was

published in the December 1987 issue of EQMM and takes place in January

1935, which gave the town of Northmont a much needed break from death and

crime. Dr. Hawthorne takes his nurse, April, for a weeklong winter holiday in

Maine, but not long after his arrival a retired stockbroker is found murdered

in his log cabin. Of course, the surrounding area is covered in a blanket of

snow marked only with the paw prints of a roaming bobcat, but not of a human

predator, which begs the question how the murderer managed to enter and leave

the cabin without leaving footprints in the snow. I appreciated the fact that

Hoch tried to be original here, but the explanation seems really impractical.

It should also be noted that Dr. Hawthorne loses his nurse in this story to marriage

here and the next two stories revolve around her replacements.

"The Problem of the Thunder Room" appeared in April 1988 in EQMM and takes place in March of 1935 and May

Russo has replaced April (yes, the joke about their names is played up), but she

is deadly afraid of thunderstorms and blacks-out when they happen. May has such

an attack when a freak storm surprises the town and when consciousness returns

tells Hawthorne she had a dream about "a hammer and people being killed,"

but the problem arises when a message reaches the doctor that someone was

bludgeoned to death during the thunderstorm and a witness swear it was May –

could she had been in two places at the same time? Unfortunately, the

explanation borders on cheating and is a less successful treatment of the

whodunit-aspect from "The Problem of the Invisible Acrobat."

"The Problem of the Black Roadster" was

published in the November 1988 issue of EQMM and takes place in April of

1935. The story introduces April's final replacement, Mary Best, who came to

town during a deadly bank robbery. I did not care for this story, I'm afraid.

"The Problem of the Two Birthmarks"

appeared in the May 1989 issue of EQMM and is set in May of 1935, in

which the attempted smothering of a food poisoning victim in Pilgrim Memorial

Hospital is tied to the destruction of a ventriloquist’s dummy of a restaurant

entertainer and a murder by strangulation in a locked and unused operating room

– to which the only key was in possession of a doctor with a cast-iron alibi.

However, the locked room turns out to not be a locked room at and is somewhat

of a cheat. Hoch seems to have been plain out of ideas during this period,

which is especially noticeable in the next story.

"The Problem of the Dying Patient" was

published in December 1989 in EQMM and takes place in June of 1935. Dr.

Hawthorne gives an elderly patient her medication and she washes the pill away

with a swig of clean water, but immediately afterwards dies of what is later

determined to be cyanide poisoning – which may cost Hawthorne his license to

practice medicine and is even suspected of a mercy killing. What I found so

immensely disappointing was how the poisoning was presented, as a genuine and

baffling impossibility, but the explanation revealed she had something in her

mouth prior to swallowing away her medication. It was explained that the item

in her mouth was slowly dissolving during her medical examination and, "when

it dissolved enough," the cyanide was released and killed her. However,

there were no remnants of this item found in her mouth or stomach during the

post-mortem? The only thing that makes the story worth a read is the situation

Hawthorne finds himself in, but not for the plot, which is atrocious.

"The Problem of the Protected Farmhouse"

originally appeared in the May 1990 issue of EQMM and takes place in the

final quarter of 1935. A local and paranoid Nazi-sympathizer, Rudolph

Frankfurt, fortified his farmhouse to protect himself from anti-Nazi elements –

effectively living "behind an electrified fence and locked doors" that's "guarded by a dog." However, an axe-wielding murderer managed to bypass

those security measures, but the explanation is simply practical and

workman-like instead of original and inspired.

"The Problem of the Haunted Tepee" was

published in the December 1990 issue of EQMM and takes place across two

centuries, which stretches from the Old West of the late 1800s to New England

of the mid-1930s. Because this is a crossover story! Ben Snow had "been a

cowboy during the 1880s and '90s" and a selection of his adventures were

gathered in a volume entitled The

Ripper of Storyville and Other Ben Snow Tales (1997), but there was one

unexplained episode from his career that has always haunted him. Snow has heard

of Hawthorne's "reputation for solving impossible crimes" and decided to

tell him the story of a haunted tepee that either killed its occupants or made

them sick. It's a nifty variation on the "Room That Kills" theme with lots of

historical color that brought a two completely separate series-characters,

which is something I love as much as a good locked room mysteries. There are

simply not enough crossovers in our genre!

"The Problem of the Blue Bicycle” appeared

in the April 1991 issue of EQMM and took place in September 1936, which

centers on a girl who went missing as if something from the sky had plucked her

from the bicycle. It's an OK story, but nothing special or particular

interesting.

Well, that was the final entry in this

collection, but I seem to have been slightly more positive when judging the stories

on an individual basis. However, the collection as a whole remains the weakest

of the three, which is a real shame. I also wish I could've begun this year on

a somewhat more positive note, but I happen to pick some less than perfect

work. Oh well, better luck with the next one!

Now, if

you'll excuse me for a minute, I have to go into hiding, because I'm sure a

certain Hoch-fanboy will appear any moment now to point and shriek at me like

Donald Sutherland from Invasion of the Body Snatchers.